On the corner of 21st Street and Park Avenue, along the side of Calvary Episcopal Church, there runs a small fenced-in oasis of greenery amid the brownstone and concrete of the city. It wasn’t designed for people to walk in. But pigeons and mourning doves take full advantage. Also many little wren-like birds. (Trust me not to know their species.)

On the corner of 21st Street and Park Avenue, along the side of Calvary Episcopal Church, there runs a small fenced-in oasis of greenery amid the brownstone and concrete of the city. It wasn’t designed for people to walk in. But pigeons and mourning doves take full advantage. Also many little wren-like birds. (Trust me not to know their species.)  Passersby are certainly welcome to look at the Calvary garden. But most just hurry by. However, I had thirty minutes to spare before a dinner appointment in the neighborhood. Thank goodness for my trusty camera phone.

Passersby are certainly welcome to look at the Calvary garden. But most just hurry by. However, I had thirty minutes to spare before a dinner appointment in the neighborhood. Thank goodness for my trusty camera phone.

The second garden was designed for people. But not just any people.

The second garden was designed for people. But not just any people.  It’s called Gramercy Park, sits at the bottom of Lexington Avenue on East 21st Street, and occupies a whole fenced-in square block of prime Manhattan real estate. Unfortunately — and unlike Central Park far to the north, which was designed for all New Yorkers and visitors to enjoy — unless you are wealthy enough to inhabit an apartment or a townhouse overlooking Gramercy Park, you don’t get into this garden. Its four gates open only with an electronic passkey.

It’s called Gramercy Park, sits at the bottom of Lexington Avenue on East 21st Street, and occupies a whole fenced-in square block of prime Manhattan real estate. Unfortunately — and unlike Central Park far to the north, which was designed for all New Yorkers and visitors to enjoy — unless you are wealthy enough to inhabit an apartment or a townhouse overlooking Gramercy Park, you don’t get into this garden. Its four gates open only with an electronic passkey.  It’s so inhospitable there’s not even a bench or two on which to sit outside the park. If you’re tired of walking and want to rest for a few moments somewhat near “nature,” you have to perch ungracefully on the narrow curb below the ornamental black iron gates. The flowers reach out beyond the bars, as if to invite you in.

It’s so inhospitable there’s not even a bench or two on which to sit outside the park. If you’re tired of walking and want to rest for a few moments somewhat near “nature,” you have to perch ungracefully on the narrow curb below the ornamental black iron gates. The flowers reach out beyond the bars, as if to invite you in.  But the only way human beings without the electronic pass can circumvent the gates is by camera. Stick your hands between the bars and you can take pictures from inside, just as if you were really there.

But the only way human beings without the electronic pass can circumvent the gates is by camera. Stick your hands between the bars and you can take pictures from inside, just as if you were really there.

Having plenty of time, I walked all around the block-square private garden. I’d always known it belonged only to residents of the square, but had never spent any time nearby. Now as I circled it, I began to feel it wasn’t fair the park should be reserved, as it were, for the very rich.

Having plenty of time, I walked all around the block-square private garden. I’d always known it belonged only to residents of the square, but had never spent any time nearby. Now as I circled it, I began to feel it wasn’t fair the park should be reserved, as it were, for the very rich.

There are a few other encircled garden-like spaces in Manhattan, but they’re within a square of buildings, usually apartment houses. And those small “private” parks for the sole use of residents and their guests are not visible from the street. You have to enter one of the apartment houses to access them and don’t even know they exist unless you visit someone who lives there. Here, however, where I couldn’t go was in full view. I began to think of Haves and Have Nots.

There are a few other encircled garden-like spaces in Manhattan, but they’re within a square of buildings, usually apartment houses. And those small “private” parks for the sole use of residents and their guests are not visible from the street. You have to enter one of the apartment houses to access them and don’t even know they exist unless you visit someone who lives there. Here, however, where I couldn’t go was in full view. I began to think of Haves and Have Nots.  This little boy, for example, is the child of a Have. (Will he grow up with a strong sense of entitlement?) I am in no doubt that if I had purchased (had been able to purchase) a home fronting Gramercy Park — the price reflecting the value of access to a private and beautifully landscaped park — I wouldn’t want cyclists, bag ladies and tired tourists resting on “my” benches or anyone dropping cigarette butts and empty cans in “my” bushes.

This little boy, for example, is the child of a Have. (Will he grow up with a strong sense of entitlement?) I am in no doubt that if I had purchased (had been able to purchase) a home fronting Gramercy Park — the price reflecting the value of access to a private and beautifully landscaped park — I wouldn’t want cyclists, bag ladies and tired tourists resting on “my” benches or anyone dropping cigarette butts and empty cans in “my” bushes.  On the other hand, other than the little boy and his nanny, there was no one in the park except two elderly people on a bench and a jogger with white earbuds in a pink track suit going round and round the graveled inner path circling the garden all by herself. That whole square block of carefully tended plantings and flowerings was for just five people. It made me consider doing a piece called “Haves and Have Nots.” But I have no solution for issues as large as that, or even for what to do about the locked gates of the Gramercy Park garden. So I comforted myself with the thought that at least birds can get in.

On the other hand, other than the little boy and his nanny, there was no one in the park except two elderly people on a bench and a jogger with white earbuds in a pink track suit going round and round the graveled inner path circling the garden all by herself. That whole square block of carefully tended plantings and flowerings was for just five people. It made me consider doing a piece called “Haves and Have Nots.” But I have no solution for issues as large as that, or even for what to do about the locked gates of the Gramercy Park garden. So I comforted myself with the thought that at least birds can get in.  It looks better without the bars showing.

It looks better without the bars showing.  And then it was time for a luxurious early dinner across East 21st Street at Maialino, in the Gramercy Park Hotel, to which I’d been invited as a guest.

And then it was time for a luxurious early dinner across East 21st Street at Maialino, in the Gramercy Park Hotel, to which I’d been invited as a guest.  When you’re a guest, it’s ungrateful to be harboring simmering thoughts of Haves and Have Nots. Best to leave all that for another day.

When you’re a guest, it’s ungrateful to be harboring simmering thoughts of Haves and Have Nots. Best to leave all that for another day.

photographs

HISTORIC CABBAGE SOUP

StandardDon’t worry; the soup in this picture was made just a few hours ago. It’s the recipe that’s historic. I was aiming for the cabbage soup my Russian mother used to serve when I was a little girl. Since she probably learned how to make it from her mother, that would put the recipe back to the last years of the nineteenth century. (Whether or not my grandmother acquired it from my great-grandmother, thereby making the recipe even older, is purely speculative.)

Oddly, my mother always called this historic soup “borscht” even though there were no beets in it. Whatever. It tasted very good. Competitive to the end, she managed with sly evasions never to give me the recipe. Which may have been just as well, because I recall that what she did was a complicated all-day affair involving a huge pot and “goluptsi” (little birds) cooked in the soup. And complicated all-day cooking is not for me, irrespective of the taste thrill at the end. What are “goluptsi?” Big cabbage leaves wrapped around a seasoned combination of chopped meat and rice. The soup would be the opener, the little birds the main course.

So the recipe I’m referring to here is not exactly my mother’s (or grandmother’s). However, something that looked as if it would taste very much like their soup eventually showed up in “EAT!” — a cookbook published by the Parents and Teachers Association of Public School 166 (Manhattan) in March 1975. I was a P.S. 199 parent of two boys at that time and therefore felt obliged to buy “EAT!” (Especially as I had two recipes included in it myself.)

The soup in “EAT!” was called “Reena Kondo’s Cabbage Soup.” The contributor of this recipe, known to us all as Miss Kondo, had been my younger son’s kindergarten teacher the year before. She was of Polish-Jewish descent, and I am quite certain the soup recipe had come to America one or two generations prior to reaching her, probably also through the maternal line, thus escaping annihilation in the Warsaw ghetto.

Instead of goluptsi, Miss Kondo’s mother and/or grandmother had added a few pieces of cut up beef and carrots. I have omitted them. I have no recollection of cooked carrots in any maternal soups of my childhood, and my mother would never have wasted a good piece of beef by boiling it in soup. However, stripped of these decadent refinements, the following reconstructed recipe will taste remarkably similar to what I was lapping up at the kitchen table in Washington Heights in the 1930’s. It makes at least three suppers-in-a-bowl for two adults as a main course. Easy-peasy too. And remember: cruciferous vegetables are very good for you.

[P.S. If you can’t find sour salt anywhere, squeeze four or five lemons, salt the lemon juice heavily, and add the salted juice to the pot.]

RECONSTRUCTED CABBAGE SOUP RECIPE, CIRCA 1900

1 head of white cabbage

2 14 oz. cans diced tomatoes

handful (or several handfuls) of white raisins

several pieces of sour salt (to taste)

Regulär table salt (to taste)

Honey and/or brown sugar (to taste)

2 apples, peeled and cut into eighths

Cut the cabbage into small pieces or shred it. In sizeable pot, cover the shredded cabbage with cold water and add all the remaining ingredients except the apples, which should be put in towards the end. Cooking time is about two hours, but after an hour or so begin tasting and adjusting the salt, lemon juice (if you’re using it) and sweetener till you achieve a sweet/sour taste you like.

I don’t know about Reena Kondo, but my mother always served it with a big blob of sour cream on top. I use yogurt. (Goat’s milk yogurt, to be precise, but we’re peculiar. My mother didn’t know about goat’s milk yogurt.)

At the table, mix with your soup spoon. Serve with black bread, French bread, no bread.

If you were to make it tomorrow (Thursday), you’d be all set through Saturday. Who wants to be in the kitchen too often, now that it’s (nearly) spring?

A TRIP BACK IN TIME: PART II

Standard[The story thus far: In the summer of 1990, I left the United States for the first time in forty years on an inexpensive two-week tour for older travelers sponsored by the University of New Hampshire. “Inexpensive” was key for me — which explains why the destination was Salamanca, Spain, the hotel had only one star, the food was unhealthy and unexciting, the program had twenty-eight participants (too many) and I agreed to share a room with a stranger. It wasn’t all a disappointment though. R., my luck-of-the-draw roommate, turned out to be terrific. And during that first trip I learned what I liked when traveling and what I didn’t. The pictures that follow are not good. They were taken by an extremely inexperienced photographer (me) with a small automatic camera on film that passed through customs x-rays twice, albeit in a lead-lined bag, and then was developed without instruction by sending it out through a drug store back home. I couldn’t crop, brighten, or edit. So what you see is what I got. But for me, anyway, these prints certainly bring the trip back. Which, aesthetics aside, is what vacation pictures are supposed to do, no?]

Because a university had sponsored the trip, there was necessarily an educational component to this vacation, which I could have done without. After all, I had already had twenty-two years of schooling, not counting nursery school and kindergarten. Nevertheless, for the first three or four days our mornings began after breakfast in a classroom: teacher, blackboard, pointer, the works. Here is “Professor Nena Lucas, N.A.” telling us what she and the colegio for which she worked thought we ought to know before we actually saw anything. Her English was reasonably fluent but heavily accented. She was twenty-six, married with two small children, and earning summer money to finish her doctorate. She was dedicated to her job with us:

I liked her. I really did. She worked so hard. But you can tell from the picture I took that I sat in the rear of the room. You also can tell from the blur what an amateur photographer I was. Anyway. Salamanca is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the Community of Castile and Leon [in northwestern Spain]. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO Heritage Site in 1988. It is the second most populated area in Castile and Leon after Vallodolid, and ahead of Leon and Burgos. 16% of Spain’s market for Spanish language study is here. It has lots of iglesias (cathedrals and churches), conventos (convents) and a Roman bridge of which fifteen arches date from the first century B.C. That’s the kind of information Professor Nena was there to provide. She also offered a brief overview of Spanish history — tactfully omitting Franco, under whose regime she must have grown up — Spanish economics, art and literature. I confess I remember none of it and just now paraphrased Wikipedia to give you an idea of what our first few mornings on the tour were like.

I counted four unattached men among the twenty-eight participants. It later turned out one of them had brought his girlfriend along so he was already part of a couple. There were also perhaps five married couples, of assorted ages but all over fifty. That left about eleven unattached women — nine if you subtract R. and me. Of the three “available” men, the one in the picture on the left worked in a monastery as a lay clerk and was with us for the religious experience, and also to improve his Spanish. Another (face hidden in picture on right) had gone on every tour the University of New Hampshire ever offered and was still unattached, which might tell you something. Then there was W., also on the right, checking me out instead of paying attention to Professor Nena. Boy, was he busy during his twelve tour days fending off attention from women, visibly playing them off against each other and loving it. Conclusion: Do not sign up for older-traveler tours to meet men! Mr. Right — or even Mr. Acceptable — generally doesn’t go for this kind of thing alone.

After the lectures, we were free to roam. There was the bridge, the two main cathedrals — old and new — and the University to see. [Shot of University at top of post.] That University, which dates from 1136, is the oldest in Spain, the fourth oldest in Europe and remains an important center of learning. A few parting words, though, about the “educational” component of non-specialized tours. (I exempt specialized programs specifically focussed on architecture, or horticulture, or Great Homes of England, or like that.) Even before the Internet, we could have found everything Professor Nena had to say in a guide to travel in Spain, and I wish the program had provided recommended preliminary reading for those who signed up and cut the “colegio” hours. It would have left more time for looking, which is what most of us, except perhaps the monastery guy, had come to do. There’s also a lot of dead time on buses — perfect for little refresher courses on whatever we might be going to see that day.

Below is what almost all architecture in the Old City looks like to the uneducated eye. I’m sure there are important architectural differences between buildings erected in different long-ago centuries, but I couldn’t tell you what they are and I’m sure no one else on the tour could, either.)

Note that one of the real difficulties in capturing an entire significant building on an automatic camera is the inability to adjust for size. Unless I was very far away, I had to do tops, or bottoms, or a detail. (Details were usually of saints.) Hence you get only a piece of cathedral here, and only a small piece of the university up at the top of the post. On the other hand, the university courtyard — with R., the American tourist in the middle of the picture, rolled-up souvenir between her white-sneakered feet — came out much better.

The camera also worked well for city scenes:

And then we hit the road. August 15 is some sort of local religious holiday in a tiny village called La Alberca. You can reach it from Salamanca in about an hour by bus.

There’s a pageant, with traditional costumes, and people who’ve come from all around the vicinity to see the show.

But the part of La Alberca I liked best was in the countryside just behind the village. Before the bus left to take us on to Miranda del Castenar (another village), I walked back there by myself. After the tumult of the procession and its spectators, it was so peaceful, quiet and green I could have sat down beneath the trees and stayed and stayed….

Instead, I took these two photographs, which are still in my bedroom, twenty-four years later, enlarged and framed:

Miranda del Castenar is a village from another time. (Although people still live there, and have cars — which spoil the view.) I’m a sucker for places like this. It has too many steps without railings for me to think of ever, in my real life, living there. Or anywhere like it. But I do love the idea of life in an earlier, simpler time. I know, I know: a time when life was, as Hobbes famously said, “nasty, brutal and short.” But isn’t travel a form of fantasy? We can never know what it’s really like to live anywhere, unless we move there ourselves. And even then, we’re “the others.” So let me have “my” Miranda del Castenar — stage set for a daydream about long ago.

But you must be tired by now. That was a lot of sight-seeing for one time. I’m tired too. (I’m not so deft at uploading photos and inserting them where I want them in a post.) So I think I’ll call it a day and try to finish up next time. Or the next two times. ( I do tend to run on.)

[To be continued]

A TRIP BACK IN TIME: PART I

StandardIn the days before digital cameras and iPhones, there was the little automatic camera, designed for the “real-camera”- challenged and also for tourists wanting to take hasty snaps of twelve-day trips covering lots of places. When departing by plane with such a camera (or even with a more complicated one), it was wise also to bring enough film to get you through the trip, because it might cost the earth if bought wherever you were when you ran out — or not be available at all, depending on location. You also needed a lead-lined bag in which to put the film when you went through customs, both before inserting it in the camera and afterwards, when you brought it home undeveloped to be turned into pictures back in the good old USA. After that, if you were industrious you invested in albums for storage of your photographed memories, carefully labeled. If not industrious, you showed them to a few people, hating how your hair looked under such hurried and often under-washed conditions, and then left them in the paper envelopes they’d come in, mysterious hints of your past for your descendants to find and puzzle over when you had passed on to a place where no cameras would be needed.

I was one of the “real-camera”-challenged. No time and light determinations for me, much less changing lenses when the tour leader was calling for a return to the bus. Not that I didn’t own a “real” camera. My newly adult children had thoughtfully provided one on my 59th birthday, just before I set off on what was to be my first travel experience outside the United States since I was nineteen. (I omit several day trips to Tijuana with my first [California] husband because he liked bullfights, a five-day honeymoon in Bermuda with my second [New York] husband, and a long family weekend in Montreal just before the oldest child went off to college. None of those required a passport, so they don’t really count.)

However, there was no time before the trip to become deft and knowledgeable with the “real” camera my children had bought, so I acquired one of the small automatic ones — a Canon, I think — as an interim measure. Also many boxes of film and the lead-lined bag. And when I got home, a large photograph album in which to mount my camera work, carefully dated and labeled, as the still practicing lawyer I then was might be wont to do.

I bring all this up, after first bringing that heavy album up the stairs to my office, because one of the things that soured my summer — besides having to edit a very long manuscript written ten years ago about a subject unpleasant to recollect — was reading about other people’s travels in their blogs while Bill and I weren’t traveling anywhere. (Yes, I am sometimes mean-spirited.) So I decided to console myself with a trip through that first photograph album. [There were many more to come.]

I hadn’t looked at that first album for a long time. The photos now seem pretty awful technically, and that’s probably not the fault of the camera. (Re-photographing the prints with an iPhone to upload them to WordPress probably didn’t help either.) But I’m glad I took them (bad as they are), saved them in the album and labeled them. They do exactly what they were intended to do: bring back the past now that I’m older (so much older) than before.

*******************

In 1990, I had been separated from my second husband for three years, had briefly recycled two old boyfriends (sequentially) with results no more satisfying than the first time, was living in a studio apartment in Boston by myself, and had just finished paying off all the credit card loans that put braces on my children’s teeth, sneakers on their growing feet, got me through three years of law school and bought me a Subaru. (In Massachusetts, you drive or you’re stuck.) I was nearing sixty and had a net worth of $0. But I had a good salary, no more college obligations for the children, and had begun to save a little something. It was time to go somewhere, while I was still young enough to do it. I renewed my passport of forty years before. Unfortunately, it was nearly summer, and I didn’t want ever-ever-ever to be in debt again. (Even though those were the days when you could still deduct all interest — not just mortgage interest — from your gross income before calculating what you owed Uncle Sam.) So whatever trip I took had to be cheap. And because it was so late, there wasn’t much choice. On someone’s advice, I wrote away to the University of New Hampshire (no email yet), which then ran a program of tours for older travelers. Their August trip was two weeks in Salamanca and northwestern Spain. By bus. If I were willing to room with a stranger, it would be even cheaper.

I spoke no Spanish and had minimal interest in Spanish culture. I also suspected that Spain in August would be extremely hot. But I was lonely. I needed company, and I needed to get away from the Uniform System of Citation and the Massachusetts Rules of Civil Procedure for a while, if only a short while. That meant I was in for Salamanca. On balance, it turned out to be a pretty good trip. Besides the copious perspiration, there were some things, identified in what follows, I could have done without. But I made a friend who’s still a friend, and laughed a lot (which I needed), and revived my interest in seeing how other people lived.

Why don’t you come along for a while?

The first thing we learned on arrival: all Spanish towns, Salamanca included, are organized around a central square. Pronounced (in Spain): Platha Mayor.

The first thing I learned on arrival: I don’t like traveling in large groups of people who have to stick together for purposes of the tour schedule. The second thing: I don’t like crowds of tourists either. I want it to be just me, me, me!!! (And chosen friends, of course.)

First good thing about the trip: My luck-of-the-draw roommate. Not because she had a “real camera.” Because we got on like gangbusters, and she’s still a friend. Even reads the blog. Sometimes.

One of the fun things R. and I did together in the hot un-airconditioned room we shared for twelve days was pee in our pants and do hand laundry at midnight. It was always blistering out (unless it was raining), we always drank a lot of water all day long and didn’t perspire it all away — and then we spent many an evening and every night in the room exchanging stories about men and laughing. We laughed so much and so hard people down the hall who heard the laughter, if not the stories, thought we had come on the trip together. If you know what laughing does to the aging sphincter of an overfull bladder, then you know what I’m talking about. If not, wait. (How long, I can’t say. But Kegel exercises or no, the day will come…..) It was a small room, with a tiny bathroom and a really minuscule sink. We had been cautioned to travel light and each had a limited supply of underwear. There was accordingly much late night washing (taking turns at the sink) and hanging wet panties on the shower rod. More difficult was a more occasional need: washing the under sheets of the two twin beds. Sometimes we didn’t. They usually dried of their own accord, if the hotel didn’t change them, which wasn’t often. Sssh…….

Hotels in Spain were then rated from one to five stars. There were no hotels without stars. So expectations for ours, Hotel Gran Via with its single star, were low. But Gran Via was clean (when we weren’t soiling it), and it tried. Pedro (I found his name in the photo album) — maitre d’, waiter and general factotum for all twenty-eight of us — was very nice. (No picture of Pedro uploaded. Sorry.)

Being a one-star hotel, Gran Via’s menu was heavy on starch, pork, and sweets. Within a few days, R. and I — trying to stay healthy — were craving something that had grown in the earth. All we could find in all of Salamanca, during what was labeled “free time” on the schedule, were”sandwiches vegetales.” White bread, a few wisps of blessedly green lettuce and — yes! –slices of fresh tomato! Here I am, thirty-five pounds heavier but twenty-four years younger than today, under the sign for the “sandwiches” — looking coy and trying with my fist to hide from the camera what might be called a slight double chin:

And now, dear readers, I fear this self-indulgent reminiscence has run on too long. Back next time with the rest of the trip, unless too many of you cry, “Enough!” Which you can do in the comment section below. I won’t be offended. Honest.

Although next time — if there is one — will be much more cultural, I assure you.

THE GIRL WHO BECAME MY MOTHER (PART VI)

Standard[Continued from five previous posts: “My mother was born on or about July 16, 1904 in or near what was then Vilna, Russia, to Vladimir Vainschtain and Berta Isaakovna Vainschtain (nee Shulman)….” When she was ten, her father died and her mother took her and her five-year-old brother to Baku, where she was sent to live with a married half-sister.]

LIFE IN BAKU. This is what I know about my mother’s life in Baku:

LIFE IN BAKU. This is what I know about my mother’s life in Baku:

School. She said she had not been a remarkable student, and did not especially like school. Her best subject was mathematics. On a scale of 0 to 5, her marks — I am using her term — were always 5 in mathematics, usually 4 in everything else. (Mathematics probably meant arithmetic, at least at first, although later it would also have had to include algebra, geometry, and maybe even calculus.) However, her academic performance was good enough to win her one of the few places reserved for Jewish girls in a “gymnasium” — one of the official schools in Tsarist Russia from which a diploma was necessary for entry to any institution of higher education. Admittance to a gymnasium — for everyone — was by examination, but the competition for the few Jewish places was fierce, especially where the Jewish population was large. According to a memorandum my father wrote of his own early life in Russia, the Jewish quota for all officially approved schools was ten percent of the student population. My father added that when his brother, five years older than he was, took the examination, there were not many Jewish families in Baku, and even fewer Jewish children, so it was relatively easy to win a place. But when the time came for him to apply, it was a different story! A flood of people had come south, fleeing first the war, then the Communist takeover in the north — and of course among them many more Jewish families. My mother was two years younger than my father; her own disclaimers about her scholastic achievement to the contrary, her performance on the entrance examination must therefore have been very good indeed.

Piano. She had wanted to learn to play the piano, perhaps because cousin Lisa had played. Lessons were available to her, but her half-sister had no piano on which she could practice. For a short while she tried to practice on the school piano after hours, when it was not in use. But this seems not to have worked out, and she soon gave up. When I was seven and she was thirty-four, my father bought a Steinway baby grand on time (monthly payments) and arranged for me to have lessons. My mother was very proud of that piano; it had the place of honor in our living room. Every day she dusted it lovingly and carefully wiped down the ivory keys one by one. But when I — the helpful seven-year-old — suggested that now we had a piano she could take lessons too and practice while I was in school, she shook her head. “No, it’s too late,” she said.

Crushes. As she entered adolescence, she lavished love on famous women opera singers and actresses. She even brought the cardboard-backed photograph of one of them to America — her favorite, I suppose. It shows a svelte woman in a floor-length dress and a long looped string of pearls looking up at the ceiling dramatically. The photograph is signed (in Cyrillic lettering) Vera Kholodnaya; I have no idea who the woman was. Perhaps a silent film star? A renowned soprano? I remember my mother singing snatches of arias from Tchaikovsky’s Eugen Onegin while she did her housework when I was little. [As a result, I can sing them, too: “Shto-tyi, Lenski, nyi tansooi-ish?” Why, Lenski? Why aren’t you dancing?]

It shows a svelte woman in a floor-length dress and a long looped string of pearls looking up at the ceiling dramatically. The photograph is signed (in Cyrillic lettering) Vera Kholodnaya; I have no idea who the woman was. Perhaps a silent film star? A renowned soprano? I remember my mother singing snatches of arias from Tchaikovsky’s Eugen Onegin while she did her housework when I was little. [As a result, I can sing them, too: “Shto-tyi, Lenski, nyi tansooi-ish?” Why, Lenski? Why aren’t you dancing?]

Appearances. One summer, she said, she had only two dresses, both white. But every day, she would wash and iron one and wear the other, so that she was always clean and neat.

Dieting. She also dieted, allowing herself every day only one small bunch of grapes and one piece of bread. [Here she would draw with her two forefingers on the kitchen table the outline of the square of bread which had been her self-imposed allotment.] She must have had iron self control. As for the length of time she maintained this spartan program, she never said. Telling me about it, when I myself was trying to slim down for college, was supposed to be inspirational. But by then I recognized a recipe for certain failure when I heard it, and did not seek further detail. My generation counted calories.

Vanity. She squeezed her feet into shoes that were too small for her because small feet, she said, were fashionable in Russia and she was vain. (It may also have been that during wartime and afterwards, pretty shoes were hard to find and you took what there was.) When I was growing up, she wore a 6 ½ and then a 7. She said that in Russia she had sometimes tried to get into a 4. As a result, she developed enormous red bunions that distorted the shape of her feet and later gave her much pain and many visits to chiropodists. It was not until she was nearly eighty that she gave up wearing stylish shoes and consented to become an old lady in sneakers.

Starvation. After the Red Army arrived in Baku in 1920, food became scarce. Soon there were no more potatoes. No more grapes. Bread was rationed. And what bread was available was so adulterated with sand she developed canker sores from malnutrition.

Romance. At seventeen, she had a boyfriend. He was blond, with light-colored eyes; his oddly combed hair featured a wave at the upper left temple. He appears at the right side of the front row of a group photograph of university students, sitting on the ground and wearing a jacket with some kind of medal hanging on it. My mother, unsmiling and plump (despite the diet), with long brown hair loosely heaped up beneath a large hat, is seated near the center of the second row.

Although they’re not sitting near each other, I know the blond one with the wave is the boyfriend because among the photographs she brought with her from Russia is a separate small photo of the same young man; the hair, wave and medal are identical.

On the back of the small photo, in pale violet writing so faint it would be illegible even if I could read Russian, is a personal message to my mother from the subject of the photograph. They saw each other for about six months, she said. Once she also told me they were engaged. I now think this means she slept with him, a confidence she would never have shared with me at the time in so many words. [After becoming a mother, she put her own past conduct behind her and adopted the two principles on which American mothers were then allegedly raising their daughters: (1) Men want only one thing; and (2) No man will marry used goods.]

On the back of the small photo, in pale violet writing so faint it would be illegible even if I could read Russian, is a personal message to my mother from the subject of the photograph. They saw each other for about six months, she said. Once she also told me they were engaged. I now think this means she slept with him, a confidence she would never have shared with me at the time in so many words. [After becoming a mother, she put her own past conduct behind her and adopted the two principles on which American mothers were then allegedly raising their daughters: (1) Men want only one thing; and (2) No man will marry used goods.]

Another loss. This fiancé was not my father. So how did they break up? (At last, a juicy part of the story!) My mother pursed her lips and smoothed the sleeve of one of my father’s dress shirts on the ironing board before sprinkling it with water from a glass. “His family was connected to the nobility,” she said. “So they arrested him.” And? The hot iron made a sizzling sound on the damp shirt. “We went every day to the prison.” She didn’t explain who “we” was. “Until we found his name on the list.” “What list?” I asked. “The list of those who had been shot. ” My mother turned my father’s shirt over on the ironing board to do the back.

MY FATHER. Not long afterwards, my mother met my father, an engineering student at the Technology Institute in Baku –probably during the summer she turned eighteen, or just before. “How did you meet?” I asked. “At university,” she answered. My father was more specific. They had mutual friends, who introduced them on the esplanade running along the shore of the Caspian Sea. Four or five months later, he managed to bring her out of Communist Russia with him. They made this exodus sound simple when I first heard of it. He asked if she wanted to come. She went to ask her mother if she should go. Her mother’s response is the only thing she ever told me Berta Isaakovna said to her. There was no equivocation: “If you can get out, get out. There’s nothing for you here.” My grandmother also sold a featherbed and a pair of pearl earrings to give my mother the money to pay her passage.

But it wasn’t simple. “Getting out” was far from easy. However, I have already written that story elsewhere. It appeared in an online magazine called Persimmontree. You can read it here, if you like. This may therefore be a good place to stop, before my mother and father reach America, speaking no English, but leaving war, hunger, and executions behind them forever.

When they were both in their early eighties and my father happy to reminiscence, I asked him once why he had invited my mother, met so recently, to come with him to America. He thought about it for a moment, smiled, and said, “I wanted sex.” I looked at my mother — that staunch advocate in my girlhood of “Men don’t marry used goods.”

“Mama, was this true?” She nodded sheepishly, and lowered her head. And never mentioned it again. But who’s to say she was wrong to succumb so quickly, and so soon after the execution of the first fiancé? I have to be glad she did, or I wouldn’t be here to tell you about it.

My mother’s experiences in America may well have further shaped the girl of eighteen who arrived on Ellis Island. But what she experienced in those first eighteen years — the repeated losses, deprivations, dislocations, fear (whether or not I have got the details quite right) — was formative. They crippled her as a person, a woman, a mother. Until she died she was afraid of “them” and what “they” might do. (You couldn’t ask who “they” were. She didn’t know.) She placed excessive value on “money,” both overly respecting and also envying those who had the security and comforts it could buy. She thought you were nothing without a man, you must do all you could as a young woman to attract one, and then once you had him devote yourself to him and his needs for the rest of your life so as not to lose him — irrespective of the cost to your own needs and happiness. She thought it was safest to stay home, it was bad to be Jewish, it was good to be beautiful. Once I was no longer a little girl, it was never easy to be her daughter. But that’s another story.

So I will leave you with one last photograph of my mother and father on the streets of New York, six months after they arrived in America. It was the summer of 1923, when she was nineteen and he was twenty-one and their whole grown-up life in a new country was still to come.

FOR MOTHERS EVERYWHERE

StandardTHE GIRL WHO BECAME MY MOTHER (PART V)

Standard [Continued from the four previous posts: “My mother was born on or about July 16, 1904 in or near what was then Vilna, Russia, to Vladimir Vainschtain and Berta Isaakovna Vainschtain (nee Shulman)….” Suddenly, when she was ten, there was no more father, no more home. Her mother took her and her five-year-old brother to Baku, where she was sent to live with a married half-sister.]

[Continued from the four previous posts: “My mother was born on or about July 16, 1904 in or near what was then Vilna, Russia, to Vladimir Vainschtain and Berta Isaakovna Vainschtain (nee Shulman)….” Suddenly, when she was ten, there was no more father, no more home. Her mother took her and her five-year-old brother to Baku, where she was sent to live with a married half-sister.]

BEING JEWISH. Berta Isaakovna’s two pre-marital conversions seem to have been concessions to the requirements of her husbands, without spiritual content. Whatever Vladimir Vainschtain might have offered had he lived, there was no religious instruction in my mother’s life. No attendance at synagogue. No ritual holiday celebrations. No prayers. No belief in God. At some point after I began to read, I learned from the books my mother purchased for me and also regularly checked out of the childrens’ library that other children said prayers at night. I thought that might be a good thing to do and asked my mother, then the source of all wisdom, how to pray. From a colored illustration of Christopher Robin at bedtime in my copy of A.A. Milne’s “When We Were Very Young,” I knew that you got down on your knees by the side of the bed, put your palms together, fingers pointing upward, lowered your head, closed your eyes, and addressed yourself to God. But who was God?

“A kind of spirit,” said my mother, trying to be helpful.

It wasn’t helpful at all. And what did you say to God?

“Whatever you like,” said my mother.

There was nothing in particular I wanted to say. I felt foolish on my knees beside the bed. And it was much warmer, and more comforting, under the covers. I soon gave up the experiment.

The papers with which she left Baku in 1922 declared my mother to be “Juive.” She regarded this classification of herself as being a mark of Cain, singling her out for bad luck and unfair treatment, and certainly nothing to advertise. It brought her no spiritual solace, no community, no source of help in troubled times. Irrespective of what she said to me about God and prayers when I asked her, she always believed in surviving on your own, no matter how difficult the problem or situation. No recourse to higher powers. “We’ll get by somehow,” she would say. With a sigh.

LISA. Her cousin Lisa arrived in my mother’s life shortly after the separation from her own mother. She must have been Berta Isaakovna’s niece, as she seems not to have been connected to the married half-sister. Always referred to by my mother as “my cousin Lisa,” she had been at what my mother called “finishing school” in Switzerland when war broke out. Somehow she managed to get back to Russia and came to live in Baku. I have the impression she stayed with or near Berta Isaakovna, at least for a while. She would have been seventeen or so when my mother, aged ten or eleven, first met her, and she made such a strong impression that I may have heard more from my mother about this idolized — and idealized? — young woman than I ever heard about herself.

LISA. Her cousin Lisa arrived in my mother’s life shortly after the separation from her own mother. She must have been Berta Isaakovna’s niece, as she seems not to have been connected to the married half-sister. Always referred to by my mother as “my cousin Lisa,” she had been at what my mother called “finishing school” in Switzerland when war broke out. Somehow she managed to get back to Russia and came to live in Baku. I have the impression she stayed with or near Berta Isaakovna, at least for a while. She would have been seventeen or so when my mother, aged ten or eleven, first met her, and she made such a strong impression that I may have heard more from my mother about this idolized — and idealized? — young woman than I ever heard about herself.

Lisa was accomplished. She spoke languages — French and German probably, as well as Russian. She could play the piano, draw and ride horses. My mother thought she was beautiful. She is not especially beautiful in the one photograph that my mother brought with her, but she does look sweet, and intelligent, and — a word my mother would have used — “refined.” Everyone liked Lisa. She was warm, and kind, said my mother, and took an interest in everything about her. Lisa was adventurous, too. When food grew scarce in Baku during the later years of the war, she took it upon herself to feed the family. She would ride her bicycle out into the country, where she bought sacks of potatoes directly from the farmers. Burdened with the potatoes, she would then manage to hitch a ride back with the soldiers on the troop trains heading into Baku. (Did they also hoist her bicycle on board?)

Listening to all this in the kitchen when I was thirteen and fourteen, usually when my mother was ironing and had time and some inclination to answer questions, I had mixed feelings about her cousin Lisa. I wanted to have what she had had, as perhaps my mother had also wanted it — finishing school, languages, horseback riding, charisma, sense of ease in the world. Lisa even had a romantic older brother, who had converted — ah, those convenient conversions in the Shulman family! — and become a Cossack. He was attached to the Imperial Family, and fell in love with the Grand Duchess Tatiana, one of the Czar’s four young daughters. When his love letters to her were discovered, he had to be smuggled out of the country in a haycart!

But I also resented my mother’s admiration for Lisa. Did she love her more than she loved me? On the other hand, how could you hate someone who had evidently been so kind and affectionate to a little cousin without any real home? Thinking about Lisa sometimes made me feel mean-spirited and selfish. Especially when I learned that although Lisa was very attractive to men, she purposely sacrificed herself for the good of the family. Beautiful and desirable, but living in perilous times, she sold herself to a wealthy and older Turkish businessman who had proposed to her, because he agreed to help her relatives with money in exchange for her hand in marriage. At this point in the narrative, I would picture lovely Lisa in a white nightgown on her wedding night, lying meekly with parted legs beneath a fat and oily dark-skinned man with pock marks and garlic breath — all to save her relatives from starvation. No objective correlative supported this unappetizing picture; my mother, who had actually seen the groom, said merely that he was “all right.”

Then Lisa and husband went away, to wherever he had come from, and there was in due time a little daughter whose photograph at age six or seven, with a big bow in her hair, Berta Isaakovna mailed after my mother had come to America. The daughter didn’t look “Turkish” at all.

Then Lisa and husband went away, to wherever he had come from, and there was in due time a little daughter whose photograph at age six or seven, with a big bow in her hair, Berta Isaakovna mailed after my mother had come to America. The daughter didn’t look “Turkish” at all.

Maybe when I grew up, we could go to Turkey and I could meet Lisa? No, my mother told me. Lisa was dead. Of tuberculosis.

How old had she been? Twenty-eight.

It’s possible my mother had no close woman friend during the rest of her long life in part because no one else could ever measure up to her cousin Lisa.

[To be continued….]

THE GIRL WHO BECAME MY MOTHER (PART IV)

Standard [Continued from the three previous posts: “My mother was born on or about July 16, 1904 in or near what was then Vilna, Russia, to Vladimir Vainschtain and Berta Isaakovna Vainschtain (nee Shulman)….” Suddenly, when she was ten, there was no more father, no more home.]

[Continued from the three previous posts: “My mother was born on or about July 16, 1904 in or near what was then Vilna, Russia, to Vladimir Vainschtain and Berta Isaakovna Vainschtain (nee Shulman)….” Suddenly, when she was ten, there was no more father, no more home.]

LOSS. My mother’s only words about losing her father were these: “My father died, and my mother took my brother and me away to Baku.” [Nearly seventy years later, I can still hear her voice as I type. Like many Russians, she could never pronounce “th” properly; it always came out as a “d.” The “o” sound in “mother” and “brother” also gave trouble; it sounded more like “ah,” as in “far.”]

Even in my early teens, this violent fissure in her childhood sounded awful to me. Had her mother taken her and her brother away because of the war?

“No. Because father died.”

What had her father died of?

“He was older than mother, and had grown children already.”

Was this an answer? Had he died of a heart attack? Cancer?

She didn’t know. “He was old.” Which must have been what she had been told at ten, and had never revisited. Rather like Vilna being forever “now part of Poland.”

And why had her mother chosen to go to Baku — so far south on the Caspian Sea?

She would shrug. “I had a half-sister there.”

It was exasperating. But at thirteen and fourteen, I didn’t know enough to ask more. And at ten, she probably hadn’t understood enough of what was happening to be able to explain, even if I had known what more to ask. Now I wonder why Berta Isaakovna could not have remained in Vilna. Had the property been sold and the proceeds divided between the widow and all the children under the terms of Vladimir’s will? Did he leave it to a grown son by his first wife, who knew how to run the business? (Was there such a son?) Did he hold the land and house as a life estate, which terminated at his death? Had he merely rented the land and house?

Or was war already rumbling on the border when he passed away, so that his widow snatched up her children and traveled as far away from the front as she could, leaving the liquidation of her husband’s estate to his lawyers? This last hypothesis presupposes Berta Isaakovna as a woman who played it safe. The German army didn’t actually reach Vilna until 1915. It’s true that between 1915 and 1918, when it was under German occupation, food shortages and discriminatory levies on the Jewish population in Vilna did make living conditions there increasingly difficult. However, if Vladimir Vainschtain died when my mother was ten, then Berta Isaakovna left the area with her children in 1914, the year World War I began but a year prior to Vilna’s occupation by German troops.

Irrespective of the real answer to the question of why mother and children moved south, which I will never know — for the little girl who was my mother it could have made no difference. All at once she lost her father, her home, her friends at school. These losses were soon compounded by another. Berta Isaakovna apparently now needed to work. After reaching Baku, she entered a military hospital as a nurse, taking five-year-old Osia with her. Ten-year-old Meera, my mother, went to live with a married half-sister, so that she “could go to school.” It’s likely that she never again actually lived under the same roof with her mother.

I don’t understand this. Osia would also have needed to go to school within a year or two of their arrival in Baku. If there was a school for him near this “military hospital,” why not one for my mother? Moreover, my mother remained in Baku until 1922, long after the conclusion of the war and even after the conclusion of fighting between the Red Army and the Whites. Why couldn’t Berta Isaakovna at some point thereafter have taken her daughter back to live with her? But there it is: as best I can tell, mother and daughter continued to live apart, although both in Baku, until my mother left for America.

This separation may not have been quite as harsh as I first thought when I heard of it as a young girl, and as it still sounds when set down without qualification. At that time, I even imagined a wicked half-sister — rather like a wicked stepmother — and a resentful half-brother-in-law.

Was her half-sister nice to her? “Oh, yes, very nice,” my mother would reply. “She had no children of her own.”

And I now think it must have been true that the half-sister was very nice, for my mother took with her to America two pictures of a small, slender dark-haired young woman, aged about twenty-five, with heavy eyebrows and round dark eyes, who — by the process of elimination and laborious translation of the inscription on the back of one of the pictures — I conclude must have been this nameless half-sister.

If I’m right, she was probably no more than thirteen or fourteen when her father married my grandmother — perhaps in part to provide her with a step-mother. She must therefore have been living at Vilna when my mother was born. Until her own marriage, she may also have been a kind of second “mama” to my mother. My grandmother’s choice of Baku as a destination after Vilna may thus have been specifically predicated on this young half-sister’s residence there with her new husband.

If I’m right, she was probably no more than thirteen or fourteen when her father married my grandmother — perhaps in part to provide her with a step-mother. She must therefore have been living at Vilna when my mother was born. Until her own marriage, she may also have been a kind of second “mama” to my mother. My grandmother’s choice of Baku as a destination after Vilna may thus have been specifically predicated on this young half-sister’s residence there with her new husband.

The second of the two photographs of this half-sister also includes (a) my mother, aged eleven or twelve, in a plain pinafore and blouse; (b) a little boy about six or seven who is probably Osia, because he is the right age and looks like photos of Osia when older sent to my mother after she came to America; and (c) another woman, seated, with a strong family resemblance to the half-sister but slightly older, whom I take to be a second half-sister.

The two half-sisters look nothing like my mother or her brother, and therefore probably take after their own mother or else their father. But this picture of brother, sister, and their two half-sisters may be what my mother considered her surviving family, since there was no separate photograph of Berta Isaakovna, her mother, in her effects after her death. Admittedly, this is all surmise. But I fear surmise is as good a recovery of the past as I am ever likely to get.

About the half-sister’s husband I can say nothing, except that he seems to have made no objection to his wife’s little half-sister living under his roof for an open-ended period of time. I have some recollection of being told that he wasn’t there much. In the army? At thirteen, I didn’t think to ask more about him. Not surprisingly, my mother volunteered no confidences.

But did that mean she never saw her mother? Yes, she saw her. When there was no school. “And I went to see her at the hospital on Sundays. I had to step over the bodies of soldiers on the floor.”

When I was eleven (in 1942) — only a year older than my mother had been when her mother left her with her half-sister — my parents moved from Los Angeles back to New York, where we all three lived in a furnished apartment in Manhattan during the summer while they searched for an affordable unfurnished place near a “good” school district. What they found was in Kew Gardens, but the lease didn’t commence until after school began. So that I shouldn’t miss the first two weeks of seventh grade at P.S. 99, Queens, my father arranged with a colleague — a Dutch Jewish violinist who had managed to extricate his family from Europe just before World War II — to put me up on a folding cot in his daughter Betty’s room for the two weeks. Betty was about my age.

Betty’s mother was pleasant to me. (Although she served stewed prunes and brown sugar on brown bread for breakfast and would not make hot cereal the way my own mother did, even when I asked.) I came home to my parents on Friday afternoon for the one intervening weekend of the two weeks. And my mother took the subway out to Queens two other evenings during each of the two weeks to have dinner with me in a neighborhood restaurant. But I missed her so much! I could hardly wait for her to come. When she finally rang the doorbell, I would fling my arms around her, my beautiful fragrant mother. And then, even while we were walking to the restaurant, and ordering, and eating, I would be counting the minutes I had left with her before she would have to go. It was all I could do to stifle the tears when she brought me back in time to get to bed when Betty did. And that was only for two weeks!

However nice her married half-sister may have been, the effect on my mother of permanent separation from her own mother, at a time when she had already just sustained major loss and dislocation, was literally unspeakable. She simply did not speak of her mother, who was my grandmother. I don’t know what my grandmother looked like, what she did, or (with a single exception, to be recounted later) what she said. The one possible photograph of her remaining in my mother’s possession when she died — if it is a picture of her, and it may have been of an aunt, her mother’s sister, who would then have been her cousin Lisa’s mother — shows a large-bosomed woman who is looking down, so you cannot clearly see her face. If it is a likeness of my grandmother, it probably owes its survival to the fact that it is also a photograph of Lisa, whom my mother adored.

At one time, I used to suppose this was a photo of my mother in her teens with my grandmother. But closer inspection of the photography studio’s mark in the lower right hand corner shows a date of ’14. In 1914, my mother was ten, so the young girl in the photo cannot be her. As the photo was important enough for her to put it in her luggage in 1922, I conclude it must be of the beloved Lisa, with either her own mother, or — less likely but possible — perhaps with her aunt, my grandmother.

I know my grandmother and mother exchanged letters and some photographs from the time my mother left Russia until the Kirov purges in 1937, after which all correspondence between the Soviet Union and the United States abruptly ceased. But when my mother learned, through revived post-World War II correspondence from my father’s family, of her own mother’s death in 1942 — she threw out all her mother’s letters. And perhaps any photographs of her mother she still had.

“How could you?” I cried when I learned — at the age of fifty-eight, long after the fact — what she had done.

“What did I need them for?” she replied, at the age of eighty-five. “She was gone.”

But once, when I was fifteen and my mother was in her early forties, deeply unhappy for a multitude of identifiable reasons (which would not have been the only reasons), and I sat in our sunken living room trying to escape her misery by reading, I saw her rise from her chair and almost run to her bedroom down the hall, where she began to cry, a thing I had never heard before. Her sobbing frightened me with its intensity. And then there broke from her a single word. “Mama!” It would have been about the time she found out that her mother had died.

[To be continued…..]

THE GIRL WHO BECAME MY MOTHER (PART III)

Standard [Continued from previous two posts: “My mother was born on or about July 16, 1904 in or near what was then Vilna, Russia, to Vladimir Vainschtain and Berta Isaakovna Vainschtain (nee Shulman)….”]

[Continued from previous two posts: “My mother was born on or about July 16, 1904 in or near what was then Vilna, Russia, to Vladimir Vainschtain and Berta Isaakovna Vainschtain (nee Shulman)….”]

LIFE IN VILNA. She was not lucky in her place or time of birth. However, until war erupted in 1914, when she was ten, her life in Vilna seems to have been peaceful. Two photographs of her survive from this period, both taken in a studio by a professional photographer. In the earlier picture, she appears to be no more than three, a solemn little girl posed in front of a low plaster wall and facing directly forward. She is dressed in a long semi-fitted wool redingote that reaches almost to her ankles; it has a scalloped edge running along an asymmetrical single line of buttons from collar to hem and is trimmed with deep cuffs of ornamented velvet and a wide pointed ornamented velvet collar. She also wears softly crushed little leather boots buttoned up the side; they disappear beneath the hem of the redingote. On her gently curling hair, parted in the middle, is a brimless velvet cap, presumably the same color as the velvet collar and cuffs of her coat. She holds a small riding crop in her left dimpled hand.

Someone has told her to stand quite still and look straight at the camera; she is taking this instruction very seriously. The photograph is in muted shades of grey, so one can’t see the color of her coat and cap, but I know that those clear round eyes are brown and that, at this age, her hair is still light, if no longer blonde. She already has the finely shaped upper lip I used to admire as she applied lipstick to it in the bathroom mirror when I myself was a little girl. And even though this photograph was taken more than a hundred years ago, I see in it also the distinctively low round baby cheeks which skipped two generations to reappear when he was little in my younger son’s first-born child, her great-grandson — whom she did not live to know. Beautifully dressed and cared for, and (I think) much loved, little Musia — or Musinka, as they would have called her –looks gravely at me across the one hundred and seven years that separate us. I wish I could hug her and protect her from what lies ahead. But of course I cannot.

By the time of the second photograph, she is eight or nine and has a baby brother, five years younger. His name? Osia, she told me. Osia is the diminutive of Osip (Joseph). But I learned that later, from reading Russian novels in translation. Not from her.

In this second picture, taken in the summer — a birthday portrait perhaps? — she is turned slightly to her right, so that the camera captures her in seven-eighths view, leaning on her crossed forearms on a low table and gazing into the middle distance. A narrow white silk ribbon is fastened across the top of her head, with a flat bow at each temple and two short trailing ends descending along each side of her chin-length wavy hair. Her dress is white cotton, the loosely tucked sleeves generously bordered at the elbow with white-on-white eyelet flower embroidery, the collarless and nearly transparent front yoke a wonder of more white-on-white eyelet flower embroidery with even narrower silk ribbons run through its borders, a bow at each side. And below the yoke, the dress becomes a loose cascade of tiny vertical crystal pleats — delicious to wear in the Russian heat, and probably very difficult to iron in those days before electric steam irons. She wears a small medallion ring on the fourth finger of her left hand.

But her enigmatic expression is the focus of this portrait. She seems somewhat sad. It may be that her eyes have already acquired the characteristic look with which I am familiar – pupils positioned high between her upper and lower lids, so that the white beneath the bottom of each pupil is clearly visible, a look which suggests tragedy even where it may be simply genetics. Or perhaps she is impatient for the posing to be over. It’s clear she’s hot; her hair is damp at the hairline and forming curls from perspiration. But she’s also resigned to the length of the photography session. Yes, “resigned” — to what she cannot help — may be the operative word here. Although not yet ten, she already looks like the mother I once knew.

These two photographs are all I have of my mother’s life in Vilna. Just as she never spoke of her father, so she never spoke of that early time except once, when pressed for details, to say she had had a pony. She must at some point also have gone to school, in all likelihood a private school to which Jewish girls were freely admitted, upon payment of the tuition, because I recall her saying that she was later able to earn a place in the “gymnasium” (pronounced with a hard “g” and an “ah” sound) — which had a Jewish quota — only when she entered the “fifth class.”

However, there is one more photograph, in faded brown sepia, which she brought out of Russia together with the very few family pictures she was able to take with her; later, in the United States, she pasted this third photograph on an 8 ½” by 11” sheet of paper, perhaps to preserve it despite its worn fragility.

The photograph shows at its center a wide driveway bordered on both sides by tall trees in full summery leaf. The driveway leads from the viewer to two wooden doors folded back and open to a cobblestone street; along the other side of the street and perpendicular to the driveway runs a low fretwork fence. It’s hard to make out what lies beyond the fence. A quiet brook? Grassy woods? In the pale far distance, behind the brook or grassy woods, rise four onion domes of varying heights, each topped by a slender spire faintly piercing the sky with the Russian Orthodox cross. My mother made no notation on the paper mounting of the photograph. She didn’t have to; she knew where that driveway was. I know only that in all likelihood it was not in Baku, even then a major city, and that the fragile photograph meant enough for her to take it with her to America twelve years later. Moreover, someone (whose hand I do not recognize — therefore neither my mother or my father) has written a date with a very fine pen point in the lower left corner of it: “1910.”

I therefore like to think this fragile sepia photograph my mother brought halfway around the world and kept for the rest of her life is a faded representation of the view from inside the driveway at Vladimir Vainschtain’s estate near Vilna, where once upon a time she had lived with her mother and father and little brother, and was loved and secure, in a place that was home.

Then, suddenly, there was no more father.

And no more home.

[To be continued….]

WHY I DON’T CHECK A BOX

StandardPeople sometimes ask me — or ask us, but usually it’s some other woman asking just me — why Bill and I don’t get married. We’ve lived under the same roof and shared all expenses for the past thirteen years. So what’s holding us back?

There are several answers to this question.

- Rude: “None of your damn business.”

- Smartass: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

- Legal: Since neither of us will leave an estate substantial enough to benefit from the tax code if we were married when the first of us dies, marriage offers no financial advantage over not being married.

- Religious: Bill considers himself a Secular Humanist. I consider myself a-religious, although if it makes anyone more comfortable to classify people ethnically or religiously, I suppose you could call me a white Caucasian woman of Jewish parentage with no particular sense of obligation to be married before living with a man.

- Societal: We are too old to have children together, and therefore the legitimacy or illegitimacy of offspring — if anyone cares about that anymore — is a non-issue.

- Truthful: Having both been married twice before, with notable lack of success, we are probably each somewhat gun-shy. Of what? We live like man and wife. We say we’re married. We register at hospitals and doctors’ offices as husband and wife. As far as other people are concerned, only our lawyer, accountant, children, grandchildren and a few close friends know for sure to the contrary. Although we will in all likelihood be together when the first of us dies, not being married gives me, at least, a sense that I could fly the coop if I ever wanted to, that I am not a “wife” in all the unpleasant senses I have experienced in my two previous marriages, that I still have free choice, every day — even if I never exercise it.

Of course, that is all quite foolish. Every other year or so, one or the other of us raises the issue again. The one who might possibly be leaning in favor, of course. Which is always the time when the other would prefer not to. And so we are never, even hypothetically, in sync.

Nonetheless, Bill did once give me a Valentine’s Day card that asked, in French, if I would marry him. It had the two boxes you see above, one of which the recipient was to check. If I tell you the French word for “no” is “non,” you can see that the card didn’t offer much choice. I keep the card — unchecked — on our mantel, though. Because it’s nice to know you’re wanted. And also to remind him the question’s still out there, and not yet answered, and that there’s only one way to answer it, short of throwing the card away — just in case he were to change his mind.

Equally pertinent to this loopy discourse is a copy of a statuette from The Art Institute of Chicago which is also on our mantel. We gave it to ourselves as a present one Christmas. (Even though we’re both “Jewish.”) It looks good from every angle, no matter which way you turn it, which may suggest to you what I’m getting at.

I happen to like best the top and bottom versions (which are similar), perhaps because I think the female figure shows best from that angle and you can best see the alignment of the bodies. But it doesn’t really matter how they stand on the mantel. As long as we feel like that about each other, at least most of the time — and can also make each other laugh — who cares whether or not I check a box on the card?

A PLAYFUL POST

StandardA propos the speed with which time passes as one gets older (discussed in yesterday’s blog post about Marcia Angell), it seems only yesterday I bought some little-kiddy toys to have in the house for when my children might come visiting from out of town with their brand-new little boys. Bill also contributed:

[You can tell we both like red. You should see our living room!]

Yes, we also had ring stacks, and shape-sorter boxes, and baby books. But the cars are more photogenic, so let them suffice by way of illustration. We did enjoy a couple of visits. But mostly the parents (my children) brought their own toys. And then suddenly, the two little toddler boys weren’t toddlers. They wore bigger size clothes, and played with other kinds of toys.

Yes, it was suddenly. Okay, on the calendar five or six years. But I had barely gotten used to the idea of grandchildren when — before we knew it — they weren’t interested in pushing stylized cars around on the floor anymore. (Although they did like matchbox cars for a while.) We gave away the ring stacks and shape-sorter boxes and baby books to neighbors who were expecting.

But I couldn’t give away the two red cars. I mean, it was only yesterday. So now they sit on my bookcase, waiting. (Not, apparently, for another little toddler. Both of my children have assured me they are not going to provide anything like that.) One car is next to an ashtray which somehow or other made its way from a hotel in Firenze onto the plane with us. (Don’t tell, please.)

The other keeps company with a small leather cup and even smaller leather box from Italy (both also from Firenze, judging by the gold imprint inside the little cup), that my mother acquired with her employee discount at J.W. Robinson’s in the 1960s.

Is a retired lady lawyer’s bookcase any place for small red toy cars?

Actually, I do know a little boy who likes toy cars. He lives with me. However, he said I should keep the two red ones in my office, because he already has two of his own. They’re Deux Chevaux — modeled on a real Deux Chevaux (two-horsepower car) he used to drive when he was a very young man in Switzerland, long before he became a little boy in Princeton. We walked all over Montpellier (France) finding them for him. Now he has them in his own office at home.

He also has other wheeled objects to play with in his office. This one turned up at a street fair in Lisbon:

And if we cast an eye around, we find other kinds of toys as well: Kyoshi dolls from Japan, pre-Columbian figures from Guatemala. [And Freud and Einstein to figure it all out.] The Modigliani you’ll just have to overlook. I should have removed it before taking the picture, but I suppose you could consider it another sort of toy for boys.

In fact, when my grandchildren come to visit these days, they make a beeline for the stairs. “Let’s go play in Bill’s office!” they cry.

NOT JUST A NAME ON A CARD

StandardWhen in a feeble effort to throw things out, I go through souvenirs of trips Bill and I have made together since our first one to Lipsi and Turkey in the summer of 2002, I frequently find business cards given to us by people of whom I have only a scrap of recollection and whom we will certainly never meet again. Out they go: the card of a businessman with whom we chatted for twenty minutes in the Istanbul airport almost twelve years ago. (He thought digital technology was going to be big.) The card of a couple met on a train from Lugano to Geneva, who were going on to Paris. (The husband, significantly older than the wife, was the youngest of seven Jewish siblings, the other six of whom had all been exterminated by the Nazis during their occupation of France.) The card of a youngish man who taught English at the University of Vermont and was staying overnight at a bed and breakfast in Antigua, Guatemala in 2005. (He was moving on the next day to a speck of village on the shores of Lake Atitlan, where he had a cottage and his neighbor in an adjoining cottage for part of the year was Joyce Maynard, who in her youth had had an affair with Salinger.)

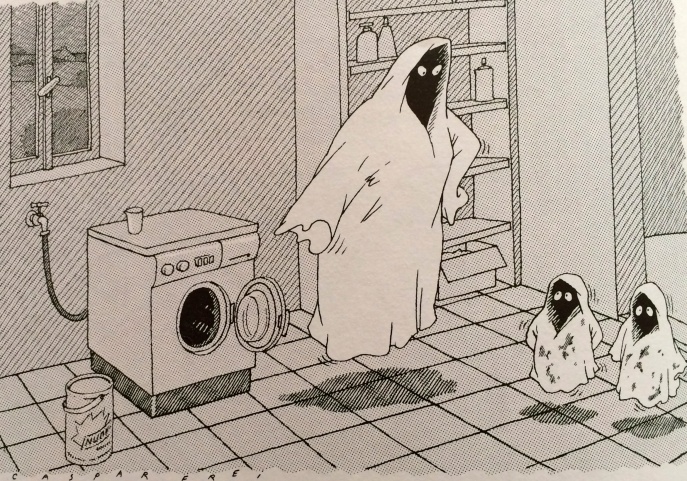

But there is a man whose card I would keep, if he had given us one. We spoke with him over a bottle of Makedonia white wine — he did most of the talking — for only two hours or so one evening in the late summer of 2002. He did offer his email address, and later (by email) his street address and phone numbers. However, we never saw him again, although we subsequently exchanged a couple of emails and he also sent us two books, one by someone else for which he had made several drawings, and the other a book of cartoons he himself had done ten or twelve years before we’d met, because we’d asked to see it.

That man’s name, and the Italian e-mail address he gave us, which may or may not still be his, remain on my computer contact list. His name, the e-mail address, a street address in Milan, one cellphone and two landline numbers also remain in a leather-bound address book I’ve had since 2002. Would any of this data lead us to him if we tried to get in touch? I have no idea. We don’t try. (What would we say?) But I don’t throw any of it out either. We might not recognize him if we were to meet him again, but we feel — I feel — we know him. He’s a friend. Because of the two hours, and the book. Sometimes life is funny like that. And who knows?

Actually, he was the one who first spoke to us. It was during our initial visit to Lipsi, a very small Greek island in the Dodecanese — a one week exploratory stay that led to four more summers there. On the fifth day of the week we took a boat tour of five speck-sized surrounding islands. Ten euros per person: what could be bad? The boat was the Margarita, the islands were Makronissi, Aspronissi, Tiganaki, Marathi and Arki. You could only get out at Marathi and Arki (and we did, but more of that another time); the other three were rocky promontories good for photography and for swimming near (but not too near). Swimming off the side of small boats was not for us. We did do a bit of photographing, though. Bill took one of me (and the arms and legs and back of some of the many Italian tourists crowding the Margarita):

I took one of a lonely-looking little boy sitting by himself:

And we both photographed the rocks and the water:

But mostly we did what both of us do best: We talked with any people who spoke a language in which we could function. On the way back after lunch and siesta on the sand at Marathi, our talk was mainly with one French couple, because neither of us speak Italian or Greek (the languages of perhaps 90% of the other tourists on the Margarita that day), but I can get by in French and Bill speaks it fairly fluently (although, say the French, with a Geneva accent). And what people who meet far from home tend to talk about, in an effort to make some connection with each other, is where else they or their families have lived or traveled. So it was with the French husband and me. We cobbled together a conversation about what had brought his parents to France from their native Latvia and what had brought my parents to New York from their native Russia. (The connection was that both his parents and my mother had come from Vilna, now Vilnius — once Russian, then Polish, then Latvian, but the same city through all the changes of nationality.) Then the Margarita reached land, we all disembarked, and we made an appointment to meet the French couple for supper at a waterside taverna the following evening, which would be our last on Lipsi.

As we stood uncertainly on the dock, not sure whether or not to head back to our not entirely satisfactory room to clean up right away, a man spoke to us, somewhat apologetically, in fluent German-accented English. He had been on the Margarita, he said, and had overheard my conversation with the French husband. He asked if I still lived in New York. I explained that I didn’t (those were my Boston years), but had grown up there and knew it very well. It seemed he had traveled extensively in the Western Hemisphere, had lived in the United States for a while, enjoyed his time there, and liked Americans very much. He wondered if we could have a drink together after supper. His wife and son were somewhat tired from the five-island excursion. They had actually done all the swimming offered at all three rocky promontories. (Quite coincidentally, the boy I had inadvertently photographed was his son, who resembled his Italian mother.) So they wouldn’t be joining us, but if we didn’t mind….

Of course we didn’t mind. And that’s how, later that evening, we got to know at least a little something about a tall, good-looking man from Switzerland who was then about fifty, and who had fallen in love with a woman from Milan, married her, and now lived there himself.