I’m not sure why I bought it. In 1962, when the book came out, Marlene Dietrich was sixty and past even her late performances in movies, which I had never much liked anyway. She always played glamorous husky-voiced European women who destroyed men. Not a good role model for a young woman who was becoming aware that her biological clock was ticking. Dietrich on the screen was definitely not a baby maker.

But by 1962, she was pretty much out of movies and performing almost exclusively in a one-woman cabaret act in large theaters throughout the world. She apparently relied on body-sculpting undergarments, nonsurgical temporary facelifts, expert makeup, wigs, and strategic stage lighting to help preserve her glamorous image as she grew older. I never saw her in this second incarnation, nor wanted to. However, she did once say in an interview that she continued with this career even when her health was failing because she needed the money.

Need is relative, I suppose; she supported her husband and his mistress until he died of cancer in 1976. They had been separated for decades, but he was the father of her only child, and she had her loyalties. She herself had by then survived cervical cancer in 1965, fallen off the stage, injuring herself badly in 1973, and broken her right leg in 1974. Her performances effectively ended in 1975 when she fell off the stage once again during an appearance in Australia and broke her thigh. By then she had become increasingly dependent on painkillers and alcohol.

After that she withdrew to her Paris apartment and refused to allow herself to be photographed, even when Maximillian Schell made a film about her (Marlene, 1984); he was permitted to record only her voice as he interviewed her, and had to rely on a collage of her old film clips for the visuals of his movie. In her early eighties by then, she sounds old, disillusioned and bitter, although still sharp. She died of renal failure in Paris at 90.

But at sixty she was not yet bitter. And her ABC is clearly hers — not the creation of some ghostwriter. The opinions in it are too idiosyncratic to have emerged from someone hired to write them for her. I may therefore have bought the book after coming upon it in a bookstore because I was then thirty years old, one year divorced after a disastrous marriage, and possibly hoping for some tips on how to manage life more productively going forward. I hope I wasn’t expecting Marlene to steer me towards the sort of second husband who would be a good father for my as yet unborn children. She would have been the wrong person for that. She was herself bisexual, wore both male and female ensembles with equal panache, and maintained short and long-term liaisons with partners of both sexes although she and her husband never divorced.

ART. A much abused word.

BACH, JOHANN SEBASTIAN. I used to love him. I practiced his solo sonatas eight hours a day. I strained the ligament of my fourth left finger. My hand was put in a cast. The hand came out weak. I was told that, with exercise, I might regain full strength of the finger but that I might not be able ever to last through a concert. I gave up the violin. I never liked Bach after that.

BACKSEAT DRIVING. Grounds for divorce.

BELLE-MERE. The French chose this word to give to the mother-in-law. It means: beautiful mother.

BODY. A heavy body weighs down the spirit.

BOOKS. You do not love a book necessarily because it teaches you something. You love it because you find affirmation of your thoughts or sanctions of your deeds.

CAUSE AND EFFECT. A logical event that no wishful thinking can erase.

CHEAP. Nothing that is cheap looks expensive.

CHEWING GUM. A pacifier for adults.

COMPASSION. Without it you mean little.

CORNED BEEF. A most persistent childhood memory is that of feasting on corned beef sent to us by our fathers serving at the front. American soldiers would throw the cans over to the enemy when the war of trenches quieted down by nightfall and the crickets made peaceful sounds — which is how my father described it in his letter.

CREDIT SYSTEM. The American Tragedy.

DAUGHTER. Your daughter is your child for life.

DEMAND AND SUPPLY. Give what is needed. “Let them eat cake” is too easy. By the same token: If nothing is needed, give nothing.

DISREGARD. With a good deal of disregard for oneself, life is a good deal easier borne.

EATING. All real men love to eat. Any man who picks at his food, breaking off little pieces with his fork, pushing one aside, picking up another, pushing bits around the plate, etc., usually has something wrong with him. And I don’t mean with his stomach.

EGGS. Scrambled: To each batch of three room-temperature eggs, add one extra yolk, salt; beat with a fork, not with an egg beater. Heat butter to golden yellow, not brown. Pour the beaten eggs into it, flame low, turn slowly with the fork. Turn out flame. Keep turning with the fork to desired consistency. Serve immediately.

EINSTEIN, ALBERT. His theory of relativity, as worded by him for laymen: “When does Zurich stop at this train?”

EMBARRASS. To embarrass anyone falls into the category of bad manners. In America, it is practiced almost like a sport.

EMERSON, RALPH W. “Do not say things. What you are stands over you the while, and thunders so that I cannot hear what you say to the contrary.” I have gooseflesh when I read this, think of this, or write this down.

FAIRY TALE. The certainty of the happy end is the magic of the tale.

FASTING. You must have an important reason to be able to fast. If you don’t, you must make an oath to yourself, an oath important enough to take the place of the important reason. Vanity is not enough of a reason. Health isn’t either, as long as you feel well. Make a time limit for the fasting. A day, for instance. It is easier to fast one day entirely than to eat a little for a week. It is very healthy to do that. Don’t think you are going to collapse on the street. Drink water and go to bed early.

FLEXIBILITY. A great asset for body and mind. In advanced age both tend to rigidity. One of the reasons why young people find it difficult to live in close contact with the old is the loss of the mind’s flexibility. Rigidity of thought, decision, opinion is by no means reserved for the old, but the danger of becoming rigid of mind increases with the years. Old people are most conscious of their stiffening bodies; they are completely unconscious of their stiffening minds.

FORGIVENESS. Once a woman has forgiven her man, she must not reheat his sins for breakfast.

GENDER. At the best of times, gender is difficult to determine. In language, gender is particularly confusing. Why, please, should a table be male in German, female in French, and castrated in English? French children, for instance, are male even if they are girls, in English there seems to be considerable doubt, in German they are definitely neuter. Even more startling is the fact that the French give the feminine gender to the components of the male anatomy that make him male, and the male gender to the components of the female anatomy that make her a female. In view of all this, let’s keep a stiff upper lip.

GENERAL DE GAULLE. The personification of my beliefs and code of conduct. When he made the unique speech in June 1940, he put me in his pocket for life. Whatever he did or said since I do not try to evaluate. He can do no wrong.

GERMANY. The tears I have cried over Germany have dried. I have washed my face. (See Israel.)

GLAMOUR. The which I would like to know the meaning of.

GOSSIP. Nobody will tell you gossip if you don’t listen.

GRANDMOTHER. Judging by the world press, I am the only grandmother alive in the world. Should there be any other grandmothers around, I salute them all. Ours is a great joy and a great task. Here are the rules: (1) We must tiptoe at all times. (2) Never tiptoe on anybody’s toes. (3) Be there when needed. (4) Never be more than ‘Mother’s helper.’ (5) disappear when not needed. (6) Bear without self-pity the silence in our own house. (7) Keep both ears cocked at all times for that call to action. (8) Be ready when it comes. (See Mother-in-law.)

GRIEF. Grief is a private affair.

HABIT. Often mistaken for love.

HANDS. I like intelligent hands and working hands, regardless of their shape in relation to beauty. Idle hands, stupid hands can be pretty, but there is not beauty in them. Of course, children’s hands are miracles from every point of view.

HAPPINESS. I do not think that we have a “right” to happiness. If happiness happens, say thanks.

HATE. I have known hate from 1933 till 1945. I still have traces of it and I do not waste much energy to erase them. It is hard to live with hate. But if the occasion demands it, one has to harden oneself deliberately. I do not think I could hate anyone who does harm to me personally. Something greater than myself has to be involved to cause me to hate.

HEAVEN AND EARTH. A great meal for summer evenings, a peasant favorite because it is good and cheap: apples (for heaven) and potatoes (for earth). Cook tart, sliced apples with sugar or, better, honey, or make applesauce. Boil potatoes, peeled or with the skin. Put two bowls on the table. Everyone has his own way of mixing the fruits of heaven and earth.

HOLLAND. Everything cozy.

HOUSEWORK. The best occupational therapy there is. It is also the most useful occupational therapy. It is one of the rare occupations that show immediate results, which is very satisfying, to say the least.

IDLENESS. It is a sin to do nothing. There is always something useful to be done. I have no respect for the idle rich who discharge their duty to be useful by staging charity balls.

ISRAEL. There I washed my face in the cool waters of compassion.

JEWS. I will not try to explain the mystic tie, stronger than blood, that binds me to them.

JOIE DE VIVRE. How few of us have it; and what a great gift for the person who has it and the people who witness it.

KETCHUP. If you have to kill the taste of what you are eating, pour it on there.

KINDNESS. Practice it; it’s easy. Just put yourself in the other person’s shoes before you talk, act, or judge.

KING-SIZE. I’m agin it.

KISSES. Don’t waste them. But don’t count them.

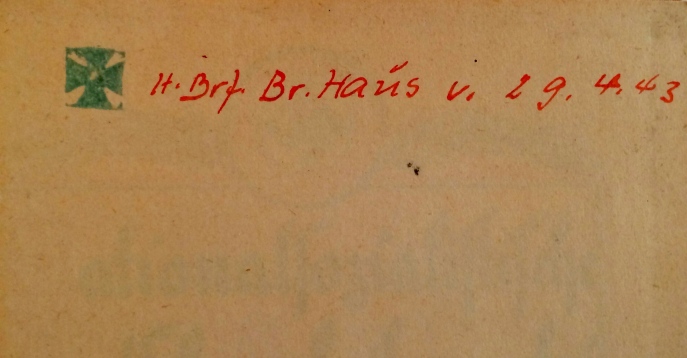

LETTERS. There is no excuse for not writing letters. My mother used to say: “Don’t tell me you have no time to write to someone who is waiting. There is a quiet place where no one disturbs you. You visit it every day — there you can write. You want to know what the place is? The emperor goes there on foot.”

LETTERS (of Love). Write them. Otherwise no one will know what wonderful feelings fill you. Even if the king or queen of your heart is unworthy (as you might have been told), write them — it will do you good. Keep copies.

LIAISON. A charming word signifying a union, not cemented and unromanticized by documents.

LIBRARY. The most precious of possessions.

LIFE. Life is not a holiday. Should you approach it thus, you will find holidays aplenty.

LIMITATIONS. Know your limitations.

LOYALTY. Should be one of the Commandments.

LUKEWARM. When this adjective applies to feelings, stop feeling whatever you are feeling.

MAILMAN. Let’s all walk. They say mailmen have no heart attacks.

MOP. An implement falsely credited with cleaning floors. (Except in the hands of a sailor.)

MOROCCO. Looks better in films.

MOTHER’S DAY. Although it might have been invented by the United Florists as a business venture, let’s be grateful to them in any case. It does remind neglectful sons and daughters to give a sign of life once a year.

MOTHER-IN-LAW. When you feel your wings grow, you’re good at it.

OPTIMISM. Have it. There’s always time to cry later.

ORDER. I need it. Emotionally and physically.

PARLEZ-MOI D’AMOUR. Yes, please do. The loving heart is a bad mind reader.

PHYSICAL LOVE. Any society that allows conditions to exist in which the adolescent begins to connect guilt with physical love raises a generation of defectives.

POLITENESS. Easy to learn, easy to practice.

POTATOES. I love them. I eat them.

POWER POLITICS. Boys playing: You-show-me-yours, I-show-you-mine.

QUESTIONS. If they are personal, don’t ask them.

QUIT. Don’t, if the goal is at all attainable. You won’t like yourself in the morning if you do.

QUOTATIONS. I love them because it is a joy to find thoughts one might have, beautifully expressed with much authority by someone recognizedly wiser than oneself.

RICH. Most rich people are pretty dull.

RUSSIAN SALAD. (One of them.) Sliced apples, sliced tomatoes, sliced onions. Salt. Children like it without dressing. You can add oil and lemon. But no other kind of salad dressing. Serve it in large bowls. Makes a very good dinner with nothing else but cheese, bread and butter.

UGLY DUCKLING. Lucky is the ugly duckling. Keep that in mind and don’t envy the pretty duckling. The dizzy pursuit of pleasure the pretty duckling easily succumbs to, does not tempt you constantly. You have time to think, to be alone, to be lonely, to read, to make friends, to help other people. You’ll be a happy swan. Just wait and see.

UP. Look there.

UTMOST. When people say, “I’m doing my utmost,” they are underestimating themselves greatly.

VACILLATION. A woman’s beauty of heart and mind renders man’s vacillating emotions constant. Her looks attract him, they do not keep him.

WAR. If you haven’t been in it, don’t talk about it.

WASTE. I hate it with a passion.

WILL. It is almost impossible to put on paper what one would want done after one is dead.

WISDOM. “For in much wisdom is much grief; and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.” Ecclesiastes 1:18.

ZABAGLIONE. Mix three yolks of eggs with three tablespoons of sugar until the mixture is creamy and whitish. Then add a bit more than half a cup of Marsala wine. Mix. In a double boiler beat the mixture with an eggbeater till it rises. Do not boil the mixture. Use a large enough pot so that it can rise almost to double the amount. If you are courageous you can forget about the double boiler and do it on a direct low flame. Serve it in wide-top glasses when it is warm.

She stained and waxed her own parquet floors. She called it one of those household occupations providing immediate results. She became an American citizen in 1939, and during the war repeatedly risked her life entertaining American troops as close to the front lines as the Army would let her go. But when the Berlin Wall came down, she left instructions in her will that she be buried in Berlin, city of her birth, near her family. After she died, her body was therefore flown there to fulfill her wish. She was interred in Friedenau Cemetery, next to the grave of her mother, and near the house where she was born.