Going to high school on the subway by myself at twelve and a half, I sometimes eyed women who looked to be about thirty and wondered if they could possibly still be doing “it.” Life disabused me of such naivete. By the time I myself neared thirty, I was newly separated from a three-times-a-week husband and found myself dying for it (no longer in quotation marks) after just a couple of weeks of abstinence.

The psychotherapist I was then seeing assured me these cravings were normal and that human sexual appetite continued practically into the grave. One of his patients was a ninety-year-old widower who had a weekly appointment with a prostitute he particularly liked. Once a week at ninety! Of course, the therapist didn’t specifically discuss what they were doing together. Nor did I care; at twenty-nine I had neither hands-on experience nor theoretical knowledge concerning the various kinds of disappointments and failures with which aging equipment too often needs to contend. Nonetheless, if in fact the therapist’s report was accurate –and why shouldn’t it have been? – these paid encounters must have produced positive results or the ninety-year-old patient wouldn’t have continued them.

Avid readers should of course recognize that such piggyback hearsay, from elderly client to psychotherapist to me to you, is not admissible evidence in a court of law. But as I myself grew older, which meant the applicant pool in which I could go fishing when unpartnered began to shrink for various reasons none of which need exploration here, I occasionally thought back to the ninety-year-old. Aging ladies, if you too are beginning to feel opportunity-challenged, take heart. The next part of my narrative has nothing piggyback about it. It’s cross-my-heart-and-hope-to-die true, and happened not so long ago either.

But first, some back story. The separation from the three-times-a-week husband occurred early in November 1960, at which time I was working on Madison Avenue as a copywriter. A client invited me to a masked New Year’s Eve ball. We were to come as our favorite eighteenth century characters. How romantic! Sure enough, as I was wandering around in my rented empire white dress (from the Napoleonic part of the century) with a white silk mask covering my eyes, there came a loud rapping at the door. A tall Venetian doge with dark hair, black cape, black mask and black staff burst in, cased the room, and found me. As explained above, I was ripe for the picking. At midnight, the masks came off. The doge, transformed into a most attractive thirty-six-year-old Harvard graduate, kissed me and took me home to my nearly bare new one-room apartment, where we danced till three in the morning to Frank Sinatra exhorting us from my portable victrola to take it nice and easy. The next day (after I had reported back to the psychotherapist, who gave provisional approval), we crossed “Go” and 1961 was off to a great start.

He had the same first name as my first husband, but that name by then brought up such odious associations that I thought and spoke of the desirable masked man only by his family name, which also made me feel quite sophisticated. (I was a very young twenty-nine.) McDonnell (let’s call him) was a terrific lover. He cared as much about giving pleasure as getting it. “I am a good cocksman,” he crowed one night, explaining how he had learned four or five years before to hold it for a long time.

He was also extremely poor husband material. Not that I was looking to marry again just yet; it would be a while before I had fully and legally untangled myself from the first husband, not to mention the time needed to recover from the emotional battering of that first marriage. But taking the long view, it must be said that McDonnell had already been married and divorced twice, and was trying to survive in Manhattan on the $6,000 a year left to him after deductions from his salary for alimony and support of the three young children of his first marriage. A philosophy major in college, he hated his job as Personnel Director of a large insurance company. He occupied a single room in a residential hotel with a good address and wore (in rotation) three gently used Brooks Brothers suits from Gentlemen’s Resale. When we went out, we often ate $3 suppers at Original Joe’s, off Third Avenue. He liked Gibsons, which were extremely dry martinis with cocktail onions instead of olives at the bottom of the glass. He probably liked them rather too much. However, he didn’t start drinking till 5 o’clock and the Gibsons never interfered with what went on in bed, so I was probably less judgmental than I ought to have been. I even kept gin and cocktail onions in the one-room apartment for him.

About a week after we met, he also sent me the most beautiful and poetic love letter I have ever received. It was written in his office when he was supposed to be working, blue ink on three pages of closely lined yellow legal paper. All I remember of it now is that we were in the Garden of Eden, and God didn’t know about us yet, and the writer of the letter was going to chase and chase me until I could run no more and fell down. It ended, “I am your you, you are my me. I love, love, love, love, love you.”

But did he ever become my me? I think not. I was certainly somewhat in awe of him, with his haut-Wasp inflections and what I thought of as his deep knowledge of the world. And especially at the beginning, I was extremely pleased and happy he was in my life. He made me feel like a desirable woman again. However, he also caused distress and then pain, probably unintentionally, by keeping me always at arm’s length, with the result that throughout the year we spent together we really led separate lives. He didn’t want to socialize as a couple (except with a few of my friends, when it was convenient for him), or to meet my parents when they came east to visit me, or to talk seriously about anything. We never spoke on the phone, except to arrange meetings. Nor do I think he ever really loved me, despite his facility with the written word. By fall, it was clear he was developing a roving eye. He began to drift off. He called less regularly. We saw each other only every other week. When I finally worked up courage to ask what was going on, he confessed he was trying to maintain two relationships at once, the newer being with a married lady. (She eventually gave him crabs.) That was it for essentially old-fashioned me. Four months later (and crab-free), he tried to come back, but the psychotherapist helped stiffen my spine. It was time to move on.

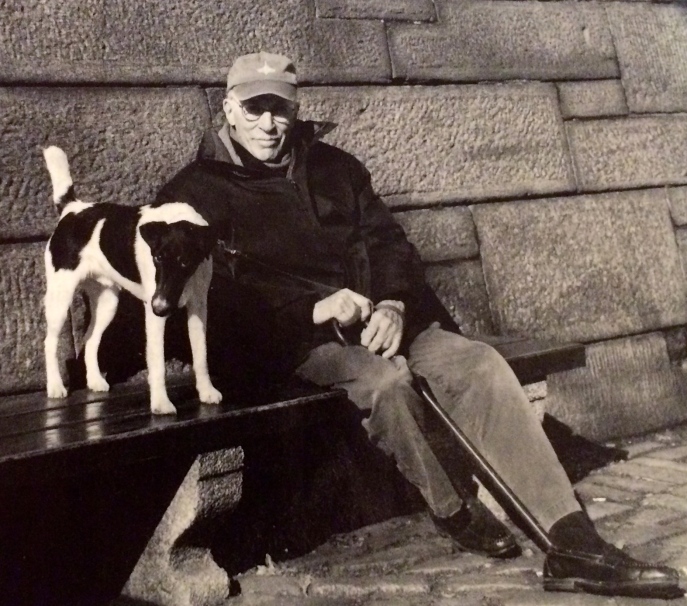

Afterwards, I spotted him on the streets of Manhattan only once, in the late 1970’s. I was now again a wife, mother of two young boys, and walking our golden retriever along the curb of West 86th Street on a Friday evening when suddenly a tall man strode swiftly towards me out of the dusk. My heart jumped with recognition. McDonnell. He looked just the same. By contrast, I looked awful – ten pounds heavier, bad hair, disheveled and damp from having made and cleared away dinner, with a stained apron still on under my unbuttoned coat. I swiveled to the side, hoping he wouldn’t see me, and he went right by, intent on his destination, which turned out to be an apartment house near Central Park. I was pretty sure there must have been a lady friend in that building. He had the eager look on his face I associated with Gibson-lubricated anticipation of a romantic interlude.

In the fall of 1995, my older son moved back to New York for a job after graduate school and I came down to visit from Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I was then living. I would be arriving before he got off work, so I needed to fill a couple of hours until we could have dinner together. Almost all my former friends had moved away, but I found McDonnell in the Manhattan phone book and called a few days before my shuttle flight. We arranged to meet for a drink at a well-known watering hole in the East 20’s. He didn’t sound especially enthusiastic, but that may be because my call came out of the blue, after (for him) about thirty-four years. However, he certainly knew my name and voice.

I was now sixty-four, he was seventy-one, and I wasn’t at all sure I would recognize him. But I knew I looked pretty good this time. I had become a well-paid lawyer, and money buys gym membership, a good hairdresser, nice clothes, tasteful makeup. I was also at liberty. Truth be told, if circumstances had been favorable I might have considered a reprise. Old friend and all that. I waited across the nearly deserted street from the appointed place until someone came along on the other side. I knew his purposeful walk at once.

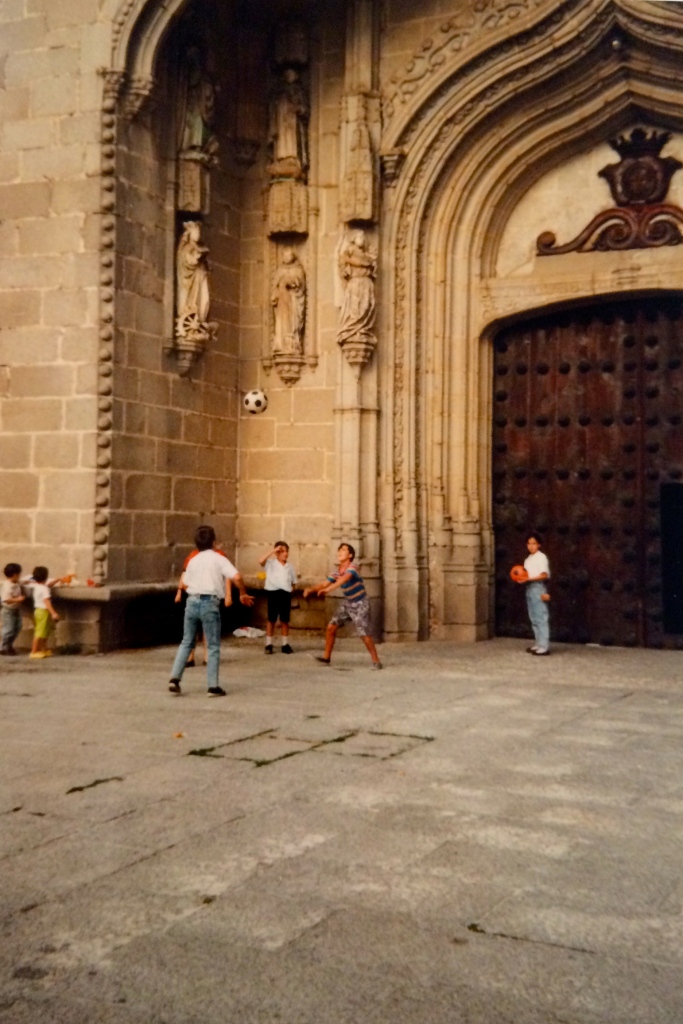

Although still trim and despite his years looking otherwise not much changed except for a few grey streaks in his dark hair, he sounded petulant over our glasses of Pinot Grigio. He was living in Brooklyn Heights with a patent lawyer of Scandinavian origins about whom he couldn’t stop complaining; she had got fat during their five years together, she was sloppy, she bought too many clothes, she had no interest in art or literature, she didn’t understand boundaries. Afterwards he filled me in on what else had been going on with him during the previous thirty-four years: a third marriage, fourth child, third divorce, grungy jobs (including night word-processing at a law firm) that permitted him to write a failed novel, and then a modest family inheritance which freed him from the necessity of supporting himself, bought him a tiny studio apartment in the East 90’s just below Spanish Harlem (then being occupied by the fourth child, now grown), and permitted him to travel a bit. He had almost no curiosity about me. We each paid for our own wine and parted with pecks on the cheek and obligatory murmurs about keeping in touch.

Although often privately critical, I am almost always loyal. Now that we had, as it were, reconnected, I began to send McDonnell seasons’ greetings most years. Each was politely but minimally answered, sometimes two months late, in a familiar handwriting which had become mysteriously tiny and crabbed. In 2000, we met for another drink, at the same place, when my son became engaged and I came to New York for a lunch given by the bride’s mother for the bridesmaids, the bride and me. His “drink” was now coffee. He’d gone on the wagon when he finally left the Scandinavian and moved back into his studio apartment. I was sixty-nine, he was seventy-six. On inquiry, he declared himself to be quite fit and well. He had also become spiritual, he said. He had a Maharishi with whom he spent summers in the Berkshires. He did yoga twice a day, took a marvelous powder every morning called Green Magma, then walked around the reservoir, rain or shine. In the afternoons, he looked after his investments and meditated. Gone were the Brooks Brothers suits and cotton oxford button-down shirts; he looked a trifle shabby in a worn pullover sweater under a tweed jacket out at the elbow. But he did have a (new) lady friend in White Plains with whom he spent every weekend. Cocksman to the end, I thought. God bless.

The following year I met Bill and we began living together. We also regaled each other with tales of our respective pasts. At seventy and seventy-three, why be coy? Eventually, we came to McDonnell. “Have him to lunch if you want,” said Bill. “If he’s ever up here to see his guru.” (Neither of us are guru-minded.) And so it came to pass that McDonnell did indeed have lunch with us in Cambridge in 2004 on his way to a summer of spirituality in the western part of Massachusetts. He was still without a perceptible stoop, and retained a full head of hair, although it had become entirely grey. (Hey, he was eighty.) He also displayed excellent company manners. It was as if there had never been anything between us. We three discussed castles in the south of France, good places to stay in Tuscany, a charming little guidebook written in French in the eighteenth century he told us about, the name of which now escapes me. There was also some chat about minstrelsy. On leaving, he pronounced the meal delightful. “Come again,” we urged. “Mmmm,” he agreed noncommitally.

Then we moved to Princeton, which is much closer to New York than Cambridge. As old friends became ill and began to die, I would occasionally mentally calculate McDonnell’s age. The year he turned eighty-four, I suggested we have lunch together the next time I came to the city to visit my new grandchildren. We settled on a day, he named a favorite place in his neighborhood, and then got a cold so the lunch never came off. I abandoned desultory efforts to stay in touch. Even stopped sending holiday cards. Time marched on. Four years after that, which was three years ago, when he was eighty-eight, he inquired by email: “Weren’t we supposed to have lunch a while ago?” I reminded him about his having had a cold and added that I didn’t come in much any more, but was going to an opera matinee in the near future and if he wanted to meet at Lincoln Center for a quick lunch at the restaurant inside Avery Fisher Hall before the curtain went up at the Met, that would be fine. It was the first time he had ever initiated a get-together. In retrospect, the fact that it was three years ago was significant.

I hadn’t seen him since the Cambridge lunch eight years before, but assumed I would still be able to spot him when he showed up. I was wrong. I waited alone in the deserted lobby of Avery Fisher for some time. Then a strange figure came up an internal staircase from the basement level. He wore a clownish red knit cap with a pompom on top, a dull grey cotton padded coat, and a green wooly scarf tied clumsily around his neck. The figure wandered about uncertainly. He was tall. Although he looked nothing like any version of McDonnell I could remember, the height decided me. Who else could it be? I rose and addressed him. The responsive voice was somewhat shaky, but the haut-Wasp inflections were impeccably in place. It was indeed he.

As soon as I identified myself, he gave me a warm and intimate smile. Of course he recognized me! He had such wonderful memories of me! Wonderful memories! He leaned forward very close, as if it were 1962. I pulled a few steps back, involuntarily. I was eighty-one. I tried to picture my twenty-nine-year-old self naked and spread-eagled on her back. “I’ll bet you do,” I said, perhaps more acidly than he deserved.

He had in the past eight years become a stranger with no recognizable similarities to any of the prior McDonnells I could recollect. When we entered the restaurant, he seemed so unsure of himself I felt I shouldn’t have brought him there. He pulled off the silly knit cap to reveal a shock of thick snow white hair. His once dark eyebrows were sparse, and he had a black mole on his neck I didn’t remember. When he slipped out of his unusual coat, I noticed a large moth hole near the neckline of the old yellow merino wool sweater he had on underneath. He didn’t know what to order. I suspected most of the offerings might be too expensive for him in his currently threadbare condition and suggested the frittata, which was the most reasonably priced. He didn’t know what a frittata was, but agreed it would be all right when he heard it was essentially Italian fried eggs. When it came, he asked me how to eat it.

I tried to bring up pleasant memories. In February 1961 he had bought me a copy of John Updike’s Rabbit Run for Valentine’s Day the week it came out and written a wouldn’t-it-be-nice-if inscription on the flyleaf: “For darling Nina, from the author.” He didn’t remember. For my thirtieth birthday, his gift had been the collected poems of Cavafy, of whom I had not yet heard. “Did I do that? Marvelous poet,” he said, accepting my Parker roll after he had consumed his own. And he had no recollection whatsoever of having hand-written the three-page love letter about the Garden of Eden. He said only one thing about our mutual past: “We were so happy. Why did it end?” I told him he had left me for a married woman who gave him crabs. The crabs he did remember. “Oh yes,” he said, wrinkling his nose in disgust. Then he shook his head a few times, presumably at himself.

I paid for my own share of the lunch; he didn’t argue or resist. At my request, he walked me across Lincoln Center to the opera house. There was another opera in my matinee subscription a month later, but when I suggested we might meet again before that performance, he gave a vague smile without agreeing. I didn’t press it. He assured me he’d be fine going home on the subway by himself. It was the last time I saw him.

But not the last time I heard from him. (Yes, we have arrived at the climax of my story!) Last December he suddenly popped up in my email box, without a subject line. By now, he was 91. I quote the email in its entirety:

Woke up thinking about you! How are you? Fondly, E__.

“What do you suppose he wants?” I asked Bill.

Bill thought McDonnell must be lonely, living alone in a grim little rear room on the third floor of a brownstone in a New York City very much changed from the years of his prime. Bill is getting up in years himself, and because he doesn’t go out much anymore he welcomes company. He had pleasant memories of the Cambridge lunch and the talk about the south of France. He suggested I invite McDonnell to Princeton for another visit. So I did.

I have reviewed the email I sent this aged man who Bill and I agreed must be lonely. In light of what followed, I was clearly too warm. I said his email was synchronicity, because I had been thinking of him too. (Not entirely a falsehood; I do occasionally check the internet to learn whether those whom I know or knew continue alive.) I inquired as to whether he could still get himself to Penn Station, issued the invitation (with instructions as to how to reach us), offered my two phone numbers, and ended unwisely: “Your little email opened the door to many memories safely tucked away in the basement of my consciousness, beginning with that masked ball on December 31, 1960. Fifty-five years ago. Ball is now in your court. I’m dancing back and forth on the service line waiting for a return.” (An instance of extending a metaphor too far.) Moreover, and much to my subsequent chagrin, I signed it, “Hugs.”

His immediate response was captioned “Fire!”

(Fire?)

Thanks for your ready response. It instantly lights a fire. I’d love to be with you and will reply more fully later tonight. E___.

Another email came two hours later, captioned “Hot!”

(Hot?)

I just left word on the two phone numbers you gave me and am dying to hear from you. E___.

So I had to call him back. It was 10:30 in the evening, rather later than people of our generation are used to calling, but if he was “dying to hear from me,” so be it. The conversation was extremely peculiar. Sounding both happy and hesitant, he said he would be glad to make the trip to Princeton but had no experience with the protocol. Protocol? I explained again where to buy a round-trip ticket, which train(s) to take, and that I’d pick him up at the station. If it was a nice day, we could have a little tour of Princeton and then come back to the house for lunch with Bill. He had met Bill in Cambridge, remember? McDonnell didn’t remember. Then he inquired into my feelings about the visit. Feelings? He pressed on: “Yes, how do you feel about me?”

“Well, I feel friendly,” I began. “What did you think?”

“No, I mean what is your mood? Is it warm?”

Oh God. “My mood? What do you want me to say, E_____? I have fond memories of you. But we haven’t known each other for more than half a century.”

“Do you want us to know each other again?”

This back and forth went on for what felt like an eternity. He assured me he hadn’t been in a relationship for three years. (Which explained his getting in touch prior to our Lincoln Center meeting three years before.) He also made reference again to our supposed past happiness together. Don’t ask how I finally managed to extricate myself.

Five minutes after we hung up, a third email arrived.

Dear Nina,

What I was hoping was that you might be in the mood for having sex with me, either chez-vous in Princeton, or here on 96th Street. I hope this directness doesn’t offend you.

That’s what I meant when I asked about the “protocol” — the having of sex with another man’s wife, in the husband’s presence (or at least knowledge), which is what I suppose a visit to Princeton might entail. (Please excuse the expression.) I’ve never done that before.

Anyway what I’d like to propose for openers is: on any day you feel like it, come to town for luncheon with me where I usually have dinner when I eat out at the Corner Cafe (they serve wine) on Third Avenue and 92nd (or so) at, 1 p.m., followed by letting me show you my apartment and so forth, and then putting you in a taxi for Penn Station.

What about it? E______.

You want to know what happened next, don’t you? Although to be desired at eighty-four is nothing to sneeze at, even if the desirer has become unappealing and the suggestion is nuts, I’ve always been serially monogamous and it’s too late to teach me new tricks now, even if I had wanted to learn them, which in this instance I definitely didn’t.

E_____,

I understood perfectly what you meant on the telephone, and thought I had disabused you of your fantasies. Apparently not.

What you propose is out of the question. I am eighty-four and have no desire to “have sex” with a nearly ninety-two year old man, whatever our relatively brief relationship may have been fifty-five years ago. Nor do I have any desire to see your apartment “and so forth.” If my email suggested anything to the contrary, you misread it.

In light of your hopes, which are entirely unrealistic and disconnected from life as I know it, I must also withdraw the invitation to Princeton.

Good luck in your quest.

Nina

At two in the morning, he replied:

I’m sorry I jumped to too many conclusions, Nina. All the best. E_____.

And thus, dear readers, I cannot provide more specifics about what this ancient lover from my long-ago past might have meant by “having sex.” Was it Clintonian sex (excluding vaginal intromission)? Would it have required assiduous oral or manual assistance from me? He was certainly hot to trot, and seemed confident all would be well, assuming my assent. I conclude from this extraordinary and entirely unexpected episode in my very late life that there must be some truth in old saws. Practice does make perfect. Sow and you shall reap. You don’t lose it if you keep using it.

Also, piggyback hearsay or no, my psychotherapist told the truth.