I was the one who bought them. It wasn’t an impulse purchase. Last Sunday afternoon, I deliberately walked to the flower shop a few blocks away. So how could this large arrangement of fresh flowers feel so wrong when unwrapped and on the coffee table?

I was the one who bought them. It wasn’t an impulse purchase. Last Sunday afternoon, I deliberately walked to the flower shop a few blocks away. So how could this large arrangement of fresh flowers feel so wrong when unwrapped and on the coffee table?

I never used to buy myself fresh flowers. Before Bill, I was working in downtown Boston all the time, and nowhere near a florist. I certainly could have picked up reasonably priced bunches of multi-colored flowers at my suburban supermarket on weekends just before checking out with a cart of groceries. But they somehow always looked unreal to me, and cheap. Besides, when would I have enjoyed them, or even have had time to change the water? I always seemed to be at the office.

Afterwards, it was Bill who brought them home. Always for birthdays and holidays, more often for no reason at all. In fact, it was unusual for there not to be a clear glass vase of fresh flowers on the coffee table in the family room where we spent most of our time when downstairs. (The clear glass was my choice; I disliked opaque containers for fresh flowers.) When they began to wilt, my frugal tendency would have been to nurse them along a little longer. He would insist on throwing them out. Then he would add “Buy flowers” to his daily list of things to do.

He especially loved sunflowers. If they were out of season, he chose lilies, preferably yellow or orange ones. He never really spent a lot. Three stems, or even two, would do for him, with as much greenery as he could persuade the lady florist to throw in for free. (He had a way with ladies.) When very occasionally persuaded to bring home roses because they were more romantic, they were yellow.

My favorite color is red. (You can see it in the chairs we bought together. He chose the designs, I chose the reds.) This made for a certain amount of mild dispute about flowers. Once he did yield: a dozen red roses on my birthday. I received them with great enthusiasm, hoping to encourage repeat performances. No such luck, even though I generally expressed somewhat less warmth than he would have liked for all the yellow, or orange, or yellow and orange it fell to me to arrange in one of our two clear glass vases.

As for the sunflowers, when we began life together they were my special bête noir. I had never liked the ubiquitous Van Gogh that shows up in all surveys of French nineteenth century painting. And I particularly disliked the large brown centers and short little petals of the sunflowers themselves. They just didn’t look flowerlike to me.

Unfortunately, at various times — either before he met me or surreptitiously afterwards — Bill had acquired about twenty stems of artificial sunflowers. They were to tide him over, I suppose, during those periods when there was a dearth of live ones. Some were close replicas of the real thing, down to the big green leaves. Others, more fanciful, were white and red, as well as yellow, with larger-than-real petals and colorful smallish centers. He also had a secret cache of objets d’art in the depths of his large office closet, from which he produced three containers in which to put nine of the fake sunflowers. (Three, three, and three.) These, after much discussion, found their way into our bedroom, to the top of the piano, and onto a sill in his office. Some of the others appeared in the finished basement in still other containers I’d never known he had, although we’d been together for over eight years at that point. The remainder of his sunflower stash I found thrust into the back of that capacious office closet when I was staging the condo to sell it; they were still waiting their chance to come into the light.

It should come as no surprise I kept them all after he died. Death changes the value of everything. In retrospect, I was sorry I’d made a fuss about them. It wasn’t such a big fuss, but still. How much I would rather have had him back with all his nutsy sunflowers, actual and artificial, than live alone in a sunflower-free apartment!

Bill’s fake sunflowers are therefore flourishing again at Windrows. Three sit in my office window: Three are on the bureau next to what I still think of as “his” side of the bed:

Three are on the bureau next to what I still think of as “his” side of the bed: Three of the most fake adorn the all-purpose table in what the Windrows architect designated as the “dining” area:

Three of the most fake adorn the all-purpose table in what the Windrows architect designated as the “dining” area: The rest are stuffed into a red (yes!) vase that sits in the living-room window:

The rest are stuffed into a red (yes!) vase that sits in the living-room window: But even with all the manmade sunflowers artfully placed here and there, up until last week my “new” apartment (not so “new” anymore) still had no fresh flowers in it, if you don’t count the two white orchids given to me on my most recent birthday by people I’ve met only in the last year. Yes, I put the orchids on my living-room windowsills away from direct sun, and yes, I keep them going, as recommended, with three ice cubes in each pot once a week. But to me they’re something else:

But even with all the manmade sunflowers artfully placed here and there, up until last week my “new” apartment (not so “new” anymore) still had no fresh flowers in it, if you don’t count the two white orchids given to me on my most recent birthday by people I’ve met only in the last year. Yes, I put the orchids on my living-room windowsills away from direct sun, and yes, I keep them going, as recommended, with three ice cubes in each pot once a week. But to me they’re something else: Art objects maybe.

Art objects maybe.  Not what I think of as “fresh flowers” though. And what’s a home without real flowers?

Not what I think of as “fresh flowers” though. And what’s a home without real flowers?

About some things I’m quick. About others not. A while ago, during a burst of sporadic early morning exercise, I passed Monday Morning, an upscale flower shop in Forrestal Village a few blocks from where I live. In the window sat a huge water bucket crammed with bunches of large-faced sunflowers, their big brown living centers turned avidly in the direction of the sun. $7 a bunch. Instead of going right into the shop as Bill would have done, I walked on by, with a smile of course – thinking how he might have run amok inside and bought two or three bunches. (One summer he gave my older son a dozen huge sunflowers in thanks for having invited us to visit in Southampton. It was hard to find a vase large enough to accommodate them all in the rented summer house.)

It took me two weeks of staring at the empty surface of the black glass table in front of the sofa. That was two weeks too many. By then only a few bedraggled sunflowers with little faces remained drooping in a small bucket at the back of Monday Morning, far from sun. Poor sunflowers. (I know: pathetic fallacy.) And now they were priced at $5 a stem, a deal breaker.

But I had come out for flowers and I’m stubborn. So what did they have in the big window water bucket this week? There was a twenty dollar bill and a credit card in the back pocket of my jeans and I wasn’t going back with nothing.

What they had, in more than one bucket, were bunches of red blooms that looked to me sort of like petunias but weren’t. That tells you how much I don’t know about flowers. Almost everything looks like petunias to me. Except sunflowers and lilies and orchids. (And pansies and daisies and carnations: I know what they look like too.) There were also bunches of carnations in all colors, including not only red, but yellow and white and red-rimmed cream. And also many bunches of greenery, some in thick-leaved silvery green, others with dark green spikes and feathery fronds. $10 a bunch; 3 bunches for $20. All very fresh and perky.

“What color do you like?” asked the saleswoman, closing in for the kill. “Her chairs are upholstered in red,” said a Windrows acquaintance helpfully; she had come out with me for the walk to Monday Morning and was now putting in her two cents.

I kept eyeing the yellow carnations. “Can I mix yellow with red?” Bill had always said you can mix anything with anything, and I always disagreed. Except now death had intervened. “Not really,” declared the saleswoman decisively, ending discussion. “Try these.” She pulled from the water a bunch of red-rimmed white carnations and pressed them against the bunch of dripping wanna-be red petunias she was already holding.

“Isn’t that nice?” she asked rhetorically. “It will go perfect with your furniture.” Really? What did she know? But it did make a third bunch of the spiky greenery free. And the greenery might help the flowers. And the carnations were a kind of orange. If you squinted. I wielded the credit card, the acquaintance peeled off for a cup of coffee, I walked back to Windrows alone with a tissue-wrapped armful. Literally an armful.

Which meant I now needed a very large glass vase. There was one, at the back of a high kitchen cabinet, which had come into my possession fifteen months before, when Bill died. It then contained an expensive condolence arrangement. Bill wouldn’t have liked this vase, even if condolences on his death had nothing to do with it. It was beyond large, and had a “fancy” shape. As I trimmed each stem and placed it in the vase, trying to mix red-rimmed carnations with red mystery flowers, I knew the whole enterprise had been a mistake. Why had I bought so many? Why had I listened to a saleswoman who didn’t know what was in my heart? Did I even know what was in my heart? What was it I really wanted? By the time I had forced the spiky greens in around the edges, and placed the completed arrangement in the center of the black glass table (see top of post), I was hating it.

Maybe it would look better if I sat on the sofa? Not really.  How could I make it look the way fresh flowers used to look on the family room coffee table before Bill died? I moved the vase off center and considered:

How could I make it look the way fresh flowers used to look on the family room coffee table before Bill died? I moved the vase off center and considered:

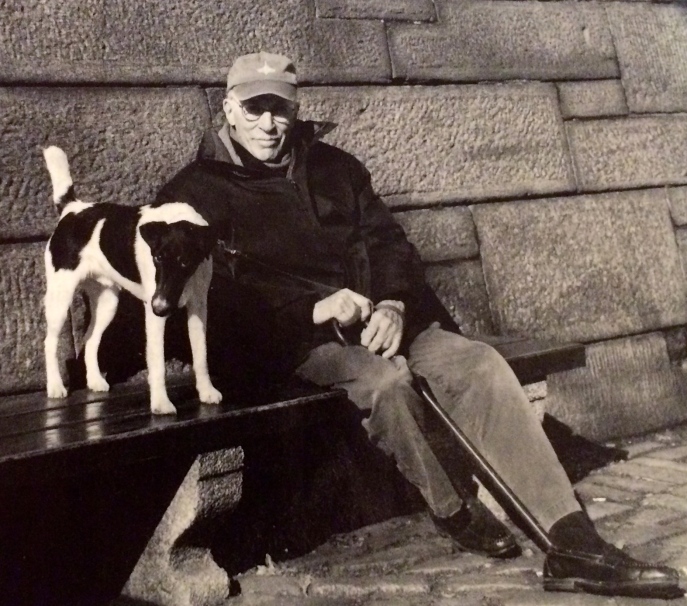

(Sophie had no aesthetic opinions to contribute here. However, as I had awakened her with all my fussing, she was plainly planning to taste the flowers when I finally went away and left her in peace. As there’s never any way I can stop her from doing most of what she wants to do, and since I was already disheartened by my purchase, I had no problem with her plans.)

The table was just too bare. In the condo, there used to be a large shiny black ceramic bowl that looked like a giant ashtray on each of our two coffee tables, one of them next to the glass vase that held the fresh flowers of the week. The bowl in the family room had a bright yellow inside surface and the one in the living room a bright red inside surface. Occasionally Bill would switch them around — “temporarily,” he said — to see if they looked better that way. I didn’t really care which was in which room as I privately thought they were both extremely unattractive (although clearly some designer’s idea of decorative “art”) and hoped for a long time, without success, that they would fall out of favor when Bill acquired something new that needed table space. It goes without saying I got rid of them both when downsizing. Now my eye was missing them. Why hadn’t I kept at least one?

What I had kept were two small black bowls of his — partly because they didn’t remind me of ashtrays but mostly because they didn’t take up much space. One was lime green inside, the other orange. I put the orange one next to the oversize vase of red and red-rimmed flowers and pushed it around a bit until it seemed to settle itself on a diagonal to the vase. It was much smaller than the shape in my memory, but it was all I had.  To cover more table top, I added a third object — my black-bound Kindle, representing the piles of books that used to accumulate wherever Bill was sitting.

To cover more table top, I added a third object — my black-bound Kindle, representing the piles of books that used to accumulate wherever Bill was sitting.

Then I pulled the flowers out of the vase as far as I could — to give them air and free them up a bit.

Bill would have said, “Enough already. Leave it. It’s fine.” And he’d have been right. This was as good as I could do. Let’s face it: I’m neater than Bill ever was. I can’t leave messes of books and papers around, even to simulate the feeling that he’s still here. My books are on shelves, my papers in files, magazines in magazine racks. I was ying, he was yang. Or vice versa. That’s why our flowers looked the way they did. And why mine look like this now that he’s gone.

The bottom line here? When these have lived out their natural life, I’m buying more. No one’s going to talk me into red ones next time. I’m going for yellow. Not necessarily sunflowers, although I’m not ruling that out. And definitely not too many, even if “many” is a bargain. They’re going to have to fit into one of my own two much smaller rectangular glass vases.

Next time I’ll also know that buying flowers, even yellow ones, won’t be like bringing him back for a while, or making the place where I live like home. It’s just as close as I can come to it. And that’s something.