Although many New Yorkers live in one of the four boroughs of New York City called Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Staten Island, it’s usually the fifth (or first) borough — Manhattan — that most people think of in connection with all the investment banking, legal and corporate shenanigans, theater, opera, music and other entertainments that originate in New York. Manhattan is also the part of New York where many movie stars live when they aren’t making movies, unless they live in Montana because they love ranching, or London because they love British rock stars, or tax havens because they love hanging on to as much of their oodles of money as they can. (Residents of New York City are triple-taxed — by the federal government, by the state, and by the city.)

However, that’s neither here nor there, so let’s move on — but not before noting it’s out-of-sight expensive to rent or buy an apartment at market rates in Manhattan these days, and that all those folks making the big bucks in finance, law, corporate shenanigans, and entertainment may have something to do with it. Deep-pocket demand outpacing supply, and like that.

There isn’t much supply left in Manhattan because it’s a sardine-shaped island positioned between the East River and the Hudson River, with its tail pointing into the Atlantic Ocean (and toward the Statue of Liberty) and its nose up in Washington Heights and Fort Tryon Park, pushing into Riverdale. The very first settlers, down at the tail, were of course the Dutch, who upon landing bought it from the resident Indians for $24 in flashy trinkets and named it Nieuw Amsterdam — or so the story goes that all New Yorkers learn in kindergarten or first grade. But the Dutch pretty soon got taken over by the English, who renamed their new property New York and began to build.

Flash forward to now. The reason demand for housing outpaces supply is that there’s no land left to build on, it’s getting harder and harder to build up higher and higher, and it costs more and more to do it. So. Back in the mid-19th century, however, there still was land, and the wealthy built north — up Fifth Avenue towards Central Park, leaving what was south of them for the hungry and desperate immigrants sailing across the ocean to find a better life for themselves. These people, first from Ireland and Germany but soon from Eastern Europe, began piling up in what we now refer to as “the lower East Side.” When you look at a map, that’s near the tail end of the sardine, on the right.

Initially, the houses there were one-room affairs built side by side. Unfortunately, this mode of construction soon became inadequate for the needs of the immigrant population, and responsive real estate investors then developed the idea of the apartment house — five-story multi-family buildings with footprints not much larger than those of the one-room houses they were replacing. These new five-story buildings were called “tenements,” and when built in the mid-1860’s were thought a great improvement over jamming ten or more people into a one-room structure.

But the multi-family buildings continued in use until 1935, by which time they were considered places to move out of as soon as one could. In any event, in that year municipal fire regulations banning the use of wooden staircases put an end to their occupation as dwellings. However, they were not destroyed because the shops on the ground floors — which didn’t rely on the staircases for access — could stay open, thereby paying for maintenance of the buildings.

Accordingly, most of them still survive, now modernized and brought up to code inside, although from the street they look much as they must have looked around 1900. Today, the Lower East Side is a place to enjoy pricey shopping and eating in historic buildings. In addition, one of the original tenement buildings — 97 Orchard Street — is now the Tenement Museum.

[The legend, which isn’t very clear in the photograph, reads: “This 1863 tenement was home to 7,000 immigrants. They faced challenges we face today — making new lives, raising families, working for better futures. Today it houses the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, which presents the history of immigration. through the personal stories of generations of newcomers who built this country.”]

And so when a few weeks ago I was invited to accompany two young children and their father on a trip to the Tenement Museum during one of the last fine Sundays before the arrival of cold weather, I was glad to accept.

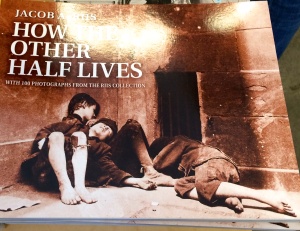

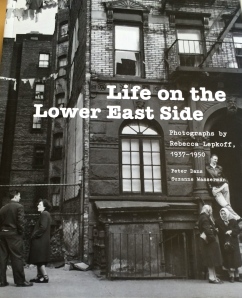

Unfortunately, one is not allowed to take photographs inside the museum. But there is a gift shop with many books of pictures, memorabilia and other trinkets for sale. Here are some of the books:

If you’re nowhere near New York and therefore unlikely to visit the museum, all of these books may be purchased online at: shop.tenement.org

There are also less instructional souvenirs, probably not worth the money — but little people do have big eyes. And it all does go to support the museum:

The museum offers eight hour-long tours, each focused on a different aspect of immigrant life in New York. One of the daytime tours is designed for children; that was therefore the one we attended the morning we went. It was about family living conditions at 97 Orchard Street.

First we met with an attractive young woman who said her name was Ellen. She spoke with the children on the tour as if she were a third- or fourth-grade teacher. (She had a blackboard, and asked the children to imagine this and that, and said “Good!” a lot.) Ellen explained the house we were in had been built in 1863-64, and had five floors, four apartments on each floor, and three rooms in each apartment. At some point in the 1920s, two toilets were installed on each floor, and pipes brought cold running water to each kitchen sink. But before then there had been no running water in the house. The only water pump was in the back yard behind the house, so all water had to be hauled upstairs in pails. The pump was next to four wooden latrines with doors. We were able to see all that as we exited, after the tour.

[Although the children didn’t hear this in the morning presentation, another tour leader in the afternoon told us that the proximity of the latrines to the well water resulted in frequent deaths at 97 Orchard Street from infant diarrhea. This second tour leader also took us up one flight of stairs, now lit but originally entirely dark and then lit by a single gaslight on the wall. The stairs were no wider than two feet from wooden banister to wall. Think of that when you learn, in the next paragraph, how many people used them to go up and down in the dark, or near-dark, several times a day.)

After writing 5-4-3-2-1 on the blackboard (for number of floors, apartments per floor, rooms per apartment, and toilets per floor in one building), Ellen asked the children how many families lived in the building. Those who knew how to multiply five times four called out the answer: Twenty! One of the adults accompanying the children on our tour then asked the average size of the families. Ellen told us that when the house was built, there were about six or seven people in each family, but later there could be as many as ten children, meaning twelve people per apartment. That meant there must have been between 120 and 240 people using the very narrow dark stairs every day — to go work or school, or to use the latrines, or to bring water, coal and food up by hand.

Ellen then asked the children to imagine that they and their parents had lived in Italy on a farm, but their parents had decided to come to America because they heard life could be better here. They could bring only one suitcase with them. What would they put in it? Would it be hard to leave everything else behind? And how would they feel in a big city, when all they had known was farm life?

After those discussions, we went to visit one of the ground floor apartments, furnished as it probably was in 1916. There we were greeted by “Victoria” — played with brio by an actress in period costume impersonating a fourteen-year-old Jewish immigrant girl from Greece. “Victoria” had been living in this apartment for three years with her family. They had arrived in 1913. She had nine brothers, but she was the only girl. However, her mother had a big belly again, so perhaps there might be another girl. Victoria was very chatty (in her strong persuasive accent), but only in response to our questions as Italian immigrants just off the boat and wanting to know something about life in America.

“Victoria” explained how ten children and two parents could sleep in three tiny rooms when there was only one double bed in one of the rooms. (The parents and the very youngest ones slept there, in the bed and on the floor.) The older brothers slept on the floor in the other room, wrapped up in rug-like pieces of cloth with a thick nap on one side. She — the only girl — slept in a similar rug-like wrap, but apart from her brothers, on the small kitchen floor.

“Victoria” also told us that children in America had to go to school till they were fourteen (this was 1916), but when she had arrived three years before they had put her in kindergarten because she didn’t know English. When she became fourteen she had only reached second grade. But her father said that was enough school and now she had to work. So she helped him make aprons three days a week, and helped her mother three days a week with all the work her mother had to do to wash and clean and cook for a family of twelve. However, one day a week was for herself. On that day, for a penny, she could see a moving picture with her girlfriend. She explained that it was a series of pictures that moved and told a story, but without words, so you didn’t have to understand the language. There was music, instead. And for another penny, she could buy an ice-cream. And for a nickel, if she saved up for it, she could once in a while ride far away to a beautiful place in the north called Central Park that was like being in the country.

Someone asked “Victoria” how much rent her family paid for their nice apartment. She said it was on the ground floor, so it cost more than the ones upstairs because it wasn’t as hot in summer and they didn’t have to bring everything up and down the stairs. That’s why it was twenty dollars a month. The ones on the top floor were only ten dollars. She also tried to impress on us how expensive it was to light the gas lamp in the kitchen: it cost 25 cents to turn on the gas meter.

We never did get around to asking about baths, or how to earn money — other than by selling from pushcarts, which was how many newcomers began. But our visit with “Victoria” was enough to give the children on the tour a vivid idea of how different her life was from theirs. She did add at the end, though, that her father was hopeful they could move north to Harlem soon, where there were more Jewish people who spoke Ladino, which was their language in Greece. Most of the immigrants at 97 Orchard Street spoke Yiddish.

After we thanked “Victoria,” said goodbye and left, Ellen offered us an astonishing additional piece of history. The real Victoria — on whom “Victoria” was modeled — did soon thereafter move to Harlem with her large family, and then later to Long Island, where she married and had two children of her own, a boy and a girl. The boy eventually became an astro-physicist who worked for NASA.

Lunch was an entirely different experience. We walked to Katz’s Delicatessen — established 1888 and verifiably kosher — at the intersection of Houston and Ludlow Streets, about four blocks away. There, as the menus printed on the paper placemats proclaimed, one could find sandwiches, on rye or “club” bread, of hot corned beef, hot pastrami, hot brisket of beef, roast beef, tongue, turkey, salami, bologna, liverwurst, chopped liver, garlic “knobel” wurst, or any combination thereof — as well as platters of any of these things — all with dill pickles and pickled tomatoes on the side. Also available were five kinds of hot knishes, potato kugel, noodle kugel, chicken noodle or matzo ball or split pea soup. Still looking? You could have a plate of lox, eggs and onions. Side dishes of steak fries, home made potato salad, coleslaw, macaroni salad and baked beans. Hot dogs and hamburgers for the kids. Seconds for anyone who had room for more.

Thirsty? No problem! Choose from Dr. Brown’s soda, celery tonic, cream soda (or diet cream soda) draught pitcher beer, Katz’s own seltzer, a New York egg cream, or one of the usual fizzy things — orange soda, root beer, cherry or grape soda, Pepsi (or diet Pepsi), 7-Up (or diet 7-Up).

Then — if you’re a bottomless pit — you could also order dessert: “New York cheesecake,” carrot cake, sponge cake, chocolate cake, one of the assorted fruit pies, or a “seasonal” cake.

[I’ve left out the “tossed green salad” (which I bet no one orders) and the assorted juices, hot or iced tea and coffee. Don’t hold it against me.]

But don’t think it’s a snap to order any of this. Remember the movie, “When Harry Met Sally?” Remember the scene where Sally fakes an orgasm over a sandwich and a lady at the next table (actually the director Rob Reiner’s mother) tells the waiter, “I’ll have what she’s having?” Remember that? That was filmed at Katz’s.

Maybe because of the movie, maybe because the servings at Katz’s are huge, maybe because Katz’s is the last of its kind — you have to FIGHT for a table:

We got lucky. As I pushed my way towards one of the few places against the wall where waiter service is available, the skinny little guy who lets people have one of them decided he liked me. He said it aloud to our small group, “You can stay here. I like her!” I blew him a kiss. “A kiss yet!” he exclaimed, wiping his hands on his Katz’s apron. “Extra pickles for the table!”

[You see? Sex — if you can call it that — works everywhere!]

Did I mention the servings were huge? Yes, I did. But I have pictorial evidence as well. I ordered a bowl of pea soup and half a liverwurst sandwich on rye. The half a sandwich was at least three inches high. Here’s the liverwurst I had to take out of it before eating it open-faced. [One of the younger members of our party ate the half slice of rye bread I didn’t want, but nobody was interested in the extra liverwurst.]

I couldn’t finish the bowl of thick homemade split pea soup or my share of the table’s steak fries either, and I’m not a dainty eater:

[The children’s father, who did manage to knock off nearly all of his hot pastrami sandwich on rye, bottom right of photo, explained he had only had a banana for breakfast and that was why he was able to finish.]

Thought I was kidding, didn’t you? Where else would a “gelato” be made artisinally, but in a “laboratorio?”

Decisions, decisions! So many flavors to choose from!

But eventually each young person got a plastic dish of two small scoops for $4.25 (plus tax), and gustatory happiness was complete. (I understand their father later explained the principle of inflation whereby “Victoria’s” ice cream cost a penny and the laboratorio’s gelato cost 425 times as much — but I wasn’t there to hear the explanation, so wouldn’t dare paraphrase. I’m sure you more or less understand the gist of it already.)

Then we waddled back to the Tenement Museum for another hour-long tour, focussed on economic issues. (It was from this second tour leader that I obtained the information provided earlier about one-room houses being replaced by “modern” tenements in the mid-nineteenth century.) We visited a second-floor apartment as it looked when occupied by its original German tenants in 1865, and there heard about the limited social support structures then in place for a family with four children when the father took off for parts unknown. After that we moved on to one of the last apartments occupied, in 1935, after electricity had at last arrived, and cold running water, too. There was a framed photograph of FDR on the wall here, and a radio looking very much like one I barely remember my parents owning when I was a small girl, and even a bathtub — although the tub was in the small kitchen, covered by a slab that served as a table when the tub was not in use; when a bath was contemplated, the slab needed to be removed and the tub filled with water heated in pots on the gas-fired stove.

But I’m sure after all that food at Katz’s, you’re in no mood for more sociology and economics. So I shall leave you on Orchard Street, gazing up at the fire escapes that were a feature of every New York apartment house, even when I was growing up:

And if you want to pick up a few more books in the museum shop before calling it a day, here are three somewhat lighter in content than the ones we looked at earlier in the day:

Don’t tarry in the shop too long, though. I forgot to mention it’s quite a walk to the nearest subway. Also it’s not so easy to find a taxi if you wait till four in the afternoon. That’s when the day guys go home and the evening drivers are just coming on duty.

But if you get out on the street and wave your arms wildly, maybe one will stop for you. Especially if you’re 83 (even if you don’t quite look it), stand straight, smile while you’re waving, and have pretty good legs. Blowing the driver a kiss as he seems to be slowing down for you can’t hurt, either. Good luck!

I’ve eaten in Katz’s on several occasions, you’re description was perfect.

The only thing I rue about since leaving NYC has been the food. Elsewhere in the good ole USA, the pizza and Chinese food are horrific, and there are no Kosher delis. 😦

I guess that’s why there’s a cooking section on my blog. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry I can’t take much credit for the Katz description. Al I did was copy the menu off a paper placemat and take some photos with the ever-handy phone. But thanks anyway.

Actually, there are some kosher delis elsewhere in “good ole” — in L.A. and probably Chicago. Also one in Boston, and one off U.S. 91 between the Mass Pike and New Haven. But looked at nationally, I agree that’s pretty slim pickings. Guess I’d better check out your cooking section! 🙂

LikeLike

It is good for us to think about what our ancestors did so that we could have a better life. I’m sure they didn’t complain about their circumstances half as much as we do today. They were true heroes.

Well-written! Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the “well written.” (The post took the better part of two days to write and edit!) With respect to your first paragraph, however, I suspect that at least the Jewish part of the immigrant population did complain; it’s in the genes. The word “qvetch” on the cover of one of the last set of books I photographed from the museum shop means just that in Yiddish!

LikeLike

Thank God I didn’t have to live there. It was a hard life but it was all they knew.

LikeLike

I’m glad I didn’t have to live there too. I’m also sure, though, that even if the immigrants hadn’t personally experienced anything better, they knew “better” was out there. They rode the trams, from which you could see the dwellings and streets of the wealthy, and “Victoria” and her friends saw early movies, in which people moved jerkily through rooms of luxury and privilege. That’s what drove everyone to work so hard — to get out of the tenements, or get their children out, as soon as possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love your trips into New York – keep them coming! The tenement scenario is very similar to the conditions in the East End of London in the same era. I see you were around the location of one of my favourite old RomComs – Crossing Delancey.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Keep them coming? Have I mentioned that door-to-door, a round-trip “excursion” to New York takes me five hours travel time? (Car, two trains, taxi to get there; taxi, two trains, car to return home.) I’m afraid that until winter goes away, there aren’t going to be many more! Nonetheless, I’m glad you’ve been enjoying them. And there’s nothing like scarcity to whet the appetite! 😀

LikeLike

I found your blog very interesting because , though I have visited New York a couple of times, I have never had the time to see this area. Your description brought it alive for me. I agree with Oldgirlnewtricks , nowadays ,we do moan about things we don’t have instead of loving the things we do. When I listen to my mother talk about the war and the important things she couldn’t get, like food, clothing and coal, I feel so blessed , especially when using my iPad . I can read instantly, news from around the world and read another person’s take on life and their experiences . Thank you. I didn’t have a telephone in our house until I was married and my husband came into some money (£300 – so not millionaires . lol. ) with which we paid for the line to be connected. Happy days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re s-o-o welcome, Margaret. And yes, the i-Pad is indeed a blessing. How else would we “know” each other?

LikeLike

Delightful, Nina!

I was especially intrigued by the bathtub-cum-kitchen counter (circa 1930s). In 1931, my parents, (with me, age 2) moved from a I-room-apartment in London to municipal housing, built 10 miles outside London (in what had been Essex marshland) for the slum-clearance population (us). This ‘modern’ house was brand new and boasted of electricity and a flush toilet, but it had just such a bathtub in its kitchen, complete with heavy removable slab top and no hot water supply –though it did at least have a drain-and-plug, a great improvement on our prior bathtub, which could only be emptied using a saucepan as a ladle, before being hung back up on the outside wall until the following weekend.

So much for the 1930s, whichever side of the Atlantic you were on… We do indeed need the occasional memory jog, to remind us how lucky we are today, in so many ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Gwen. I enjoyed writing it too, even though it took much too much time!

I myself never lived with a kitchen bathtub, and didn’t check whether the one at 97 Orchard Street had a drain and plug. I tend to think it did, though, because it was situated next to the sink. so it could drain into the same pipe. The thought of emptying a tub with saucepan and ladle is enough to put one off baths forever. We are — in many physical ways — indeed extraordinarily lucky today.

LikeLike