[This post is an experiment. It’s certainly different. Also, I suppose, educational. But long. If you hate it, please do come back tomorrow. I promise to be short. And sweet as pie….]

One of the things you’re supposed to do when you get older is throw stuff away. That’s so loved ones who survive you won’t have to do it — or fight over doing it — after you’re gone. You should start by getting rid of everything you’ve been keeping “just in case.” Then you move on to things you used to be fond of. And then…. But I haven’t got that far yet. In fact, I really haven’t even begun.

However, I do think about that first step, almost daily. “Just in case” what? Why does my basement still contain a casebook of contract law? I know the answer there: Because I liked the Contracts professor in 1982. (Nice one, Nina.) But a large manual on how to conduct depositions in Massachusetts? Do I really plan to do that ever again now that I’m retired and living in New Jersey?

Then there are several red-rope folders full of nicely bound memoranda, with colored paper covers, in support of appeals, or oppositions to appeals, to the Massachusetts Appeals Court and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The color of the paper told the court clerk — at a glance! — whether you were Appellant or Appellee, or were filing an Amicus brief. An Amicus brief is what? Never mind. You are probably confused enough already.

Who is going to read this closely argued work in the red-rope folders when I’m no longer here? One memorandum to the Appeals Court, I recall, was about who was liable for a leaky floor in a dairy. The trial court had let the installer of the floor get off without paying a red cent. The client, who owned the cows, insisted on an appeal. The argument for this exercise in futility was like an upside-down pyramid balanced on a single sentence discovered after exhaustive search of multiple bound volumes of trial and deposition testimony to the contrary. That all-important single sentence could perhaps have been construed to suggest that maybe, just maybe, the installer had had a momentary and fleeting doubt about the impermeability of one of the tiles in the floor. You’d really like to read something like that?

[Footnote : I was a second-year associate when this problematic dairy floor arrived on my desk. As the fifth-year associate who delivered it explained with a demonic grin : “Shit rolls down hill.”]

However, no legal residue in the basement compares to The Farmland Brief. Almost two inches thick, thanks to the supporting documents bound into it as exhibits, it occupies pride of place on the dusty bookshelf containing the other memorabilia heretofore described. It’s there because it poisoned two years of my life, including many weekends or parts of weekends. Why am I keeping it? Why? I wasn’t even the lead lawyer.

[Word to the wise: Here’s where you bow out until tomorrow unless you want to learn more than you ever thought you needed to know about NEPACCO II, CERCLA, Superfund sites, diversity jurisdiction in United States courts and whether the costs of cleaning up environmental contamination constitute ” damages because of property damage” within the meaning of comprehensive general liability insurance policies.]

Everybody gone yet? Okay, let’s start with NEPACCO. It’s an acronym for Northeastern Pharmaceutical and Chemical Co., and also for a case that Northeastern brought in the United States District Court for the District of Missouri to find out if it really was responsible under CERCLA for cleaning up environmental damage it had caused in the state of Missouri before CERCLA was enacted.

What is CERCLA? It too is an acronym — short for a piece of federal legislation called the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, also known as Superfund. [And if you think all this is flowing from me like ordinary speech, think again. I had to do research, as if I’d never known it, principally in a law review article which appeared in the Summer 1998 issue ofThe Missouri Law Review: “CERCLA Response Costs and CGL Policies: Insureds Find a Favorable Forum in Missouri” by Ryan S. Fehlig. Which I mention just in case anyone wants to look really deeply into any of this, a thing I very much doubt.]

The federal trial court for the state of Missouri decided that Northeastern did have do the cleaning up at the Superfund sites it had polluted before CERCLA was enacted because the law was retroactive and therefore applied to pollution already in existence. Northeastern appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit; the Eighth Circuit upheld the trial court’s decision, and that was NEPACCO I.

However, none of this concerned us, practicing law back in Massachusetts. Then came NEPACCO II!

Like all big corporations, Northeastern had for decades been buying comprehensive general liability (“CGL”) policies and excess liability policies and excess policies on top of those — millions and millions of dollars of insurance to cover property damage and personal injury and whatever. Naturally, it turned to these policies to help cover the cost of cleaning up the sites it had been stuck with in NEPACCO I.

Northeastern’s insurers all said, “NO!” You can understand why. At the time their actuaries had calculated the premiums for all those policies, cleaning up environmental damage wasn’t even a mote in anyone’s eye. No one had thought of it. So the premiums hadn’t been high enough to cover the risk of this new kind of liability.

Northeastern, or its insurers (I forget which, but it doesn’t matter), went back to the federal trial court to get this very important insurance coverage question settled. The court agreed with the insurers. On appeal, the Eighth Circuit agreed with the trial court. And that was NEPACCO II.

Now for a little lecture on jurisdiction. There are two systems of courts in the United States. Every state has at least one state trial court and one or two levels of appellate court (for appeals). These state courts decide issues of state law. (They may also decide issues of federal law, but usually the parties to a dispute about a question of federal law take their differences to federal court.)

In addition to state courts, every state has at least one federal trial court. There are also federal appeals courts, called Circuit Courts of Appeal, which take appeals from the federal trial courts in a number of states. For instance, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, which decided the two NEPACCOs, takes appeals from federal trial courts in Iowa, Arkansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota and Missouri.

Federal courts have two kinds of jurisdiction, meaning they can hear two kinds of cases. The first involves questions of federal law. The second is called “diversity” jurisdiction. If the parties to the dispute come from different — i.e., “diverse” — states, they can be heard in federal court even if the question they are arguing involves state law. To decide such state law questions, the federal court will look to state law, if there is any. But if the state has not yet decided the question before the federal court, the federal court has two choices: (1) it can send the question of law back to the state court to decide; or (2) it can try to decide what the state court would have decided if the question had come before it.

The states regulate insurance. Questions of insurance law are therefore matters of state law. The federal trial court that decided NEPACCO II, and the Eighth Circuit Court that upheld the trial court on appeal, thus looked to Missouri state law for the answer to the question of whether the words “damages because of property damage” in CGL policies covered Superfund liability. They found there wasn’t any Missouri state law about this! No Missouri state court had ever addressed the question! So the two federal courts, sequentially, decided that IF Missouri had had to decide, it would have held that the term “damages because of property damage” in CGL policies did not include the costs of environmental damage cleanup by insureds.

Oy!

Do you know what this meant to corporate polluters in Iowa, Arkansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota — as well as in Missouri? No insurance coverage whatsoever! No matter how much they had paid those big bad insurance companies for decades!

Now — at last — we come to Farmland. The woman partner I mainly worked for from 1991 until 1997 specialized in environmental insurance coverage litigation. (Fights in court between insurers and their insureds about what was covered and what wasn’t. She always represented the insureds.) Her cases were usually in Massachusetts, although there were occasional forays into the Superfund litigation wars in adjoining states.

However, in 1994 or 1995 she had the unusual and potentially lucrative idea of overturning NEPACCO II by bringing the matter of “damages because of property damage” in standard CGL policies before the Missouri Supreme Court and persuading that court that the Eighth Circuit had been wrong when it tried to read Missouri’s mind. What do you know? She found herself a Missouri plaintiff — namely Farmland Industries, Inc., Farmers Chemical Company, and Union Equity Co-Operative Exchange (collectively known as “Farmland”) — with environmental liability at seventeen sites! And Farmland had thirty-six insurers — all refusing to cough up, because NEPACCO II said they didn’t have to.

She also found some Missouri lawyers willing to sponsor her for one-time admission to the Missouri bar (pro hac vice is the technical term) — for purposes of representing Farmland in this challenging enterprise. And she persuaded me to help her get through it. “Persuaded” is a euphemism; I really had no choice. In addition, we had a senior associate, a junior associate, three paralegals, an insurance policy specialist, secretaries for everyone, and the night word processing department. A whole army! This was a round-the-clock operation — everyone industriously billing time at an obscene number of dollars per hour.

Back to those seventeen sites: They weren’t all in Missouri. In order to stay in Missouri state court and not get transferred to federal court (where diversity jurisdiction and NEPACCO II would apply), the woman partner cleverly persuaded Farmland to settle with thirty-two of its insurers, so that only five of the original seventeen sites — all in Missouri — and only four insurers remained in the litigation.

Now there was no more diversity between the parties. So the defendants couldn’t get the case transferred out of the trial court of Clay County, Liberty, Missouri and into federal court (where they wanted it).

I will not describe the next year or so. We had to analyze every single case ever decided anywhere in the United States on this question and sort them into two baskets: one a basket of decisions for us, and the other a basket of decisions that the federal trial court and Eighth Circuit had relied on to come up with NEPACCO II. (“Basket” is a metaphor, you understand. There were no baskets. Only piles of photocopies of decisions highlighted in yellow all over everyone’s floors so there was nowhere to walk.) Then we had to show how every single case in the second group differed from Farmland’s situation and explain to the state court (respectfully but forcefully), case by case, why the federal court was wrong to put its eggs in the second basket.

There was a lot of writing and rewriting. The woman partner who had stirred up this hornet’s nest was nervous, because the monthly bills for legal services to Farmland were very high, and mounting higher, and Farmland was understandably restive. Thanks to her, we were rewriting until eleven and twelve o’clock at night. Each rewrite had to be proofread. Ever hear of The Uniform System of Citation? You’re lucky. It regulates every single comma and period and space after a period in every single piece of legal writing. And regulates many other things in that writing as well. We had to comply with its regulations. On each rewrite. And you thought the practice of law was glamorous! I thought I’d go blind!

Also, everything we wrote that the woman partner finally approved of — after changing her mind three or four times — had to be filed in Missouri by Missouri counsel. Which means it had to be sent to Missouri counsel in time for them physically to get it to court before court closed on the last day for filing. Fed Ex stopped picking up in Boston for next day delivery to Missouri at 11 p.m. After that, there was a service called Mercury, but they didn’t pick up; you had to get your stuff to them by 2 a.m.. I think that job was relegated to the senior associate, who was a man. Poor guy, wandering the dark streets of Boston with our precious legal memoranda and appendices at 1:45 in the morning.

We were all very tense and sour, and snapped at loved ones, and the money didn’t make it better. Then we lost. On something called a summary judgment motion — which means it was all on paper to the court. (No trial or witnesses or any of the good stuff. Just paper.) Farmland of course appealed, since that had been the plan in the first place. The case was transferred to the Missouri Supreme Court before the Missouri Court of Appeals could issue an opinion.

And the nightmare began all over again.

It lasted another year. But at last there was oral argument. By our woman partner. The Missouri Supreme Court is in Jefferson City, the fifteenth largest city in Missouri. It has nothing of interest in it except the State Capitol, the State Supreme Court, the State Penitentiary (in a rather attractive building), and one hotel for all lawyers arguing cases before the Court. It is in the geographic center of the state, and does not have an airport. We flew to St. Louis, and drove to Jefferson City by limousine. We passed a llama farm. The limousine driver explained that llama was going to be the coming meat in expensive restaurants. He said this in 1996. He was apparently wrong.

I spent the evening before oral argument in the woman partner’s hotel room, watching her try on each of the three skirt suits she had brought and helping her decide which of the three was most persuasive. We chose the navy blue; she was short and blonde, and it made her look like a sweet lay nun. Next day, in navy, she argued our case before seven Missouri justices. By now she knew it forwards, backwards, sideways. You could interrupt her with questions, and she didn’t bat an eye. She looked small and pure. Counsel for the insurers were loud and large and blustery and thought they could shout her down.

You can’t shout down pure. We won. NEPACCO II was no longer good law in Missouri! [See Farmland Industries, Inc. v. Republic Insurance Co., et al., 941 S.W.2d 505 (Mo. 1997).] Insurers would hereinafter have to pay through the nose for Missouri environmental cleanups! As for us, we could clear the floors, bundle up all the paper, send it away to Dead Storage and go out for a celebratory dinner.

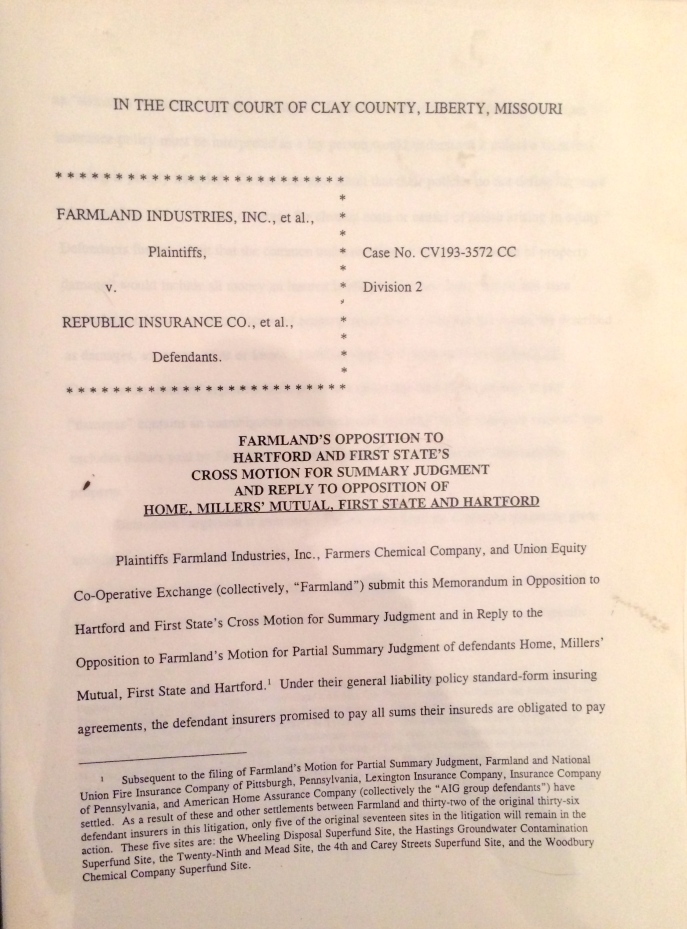

But for sixteen years I’ve kept a copy of the victorious Farmland Brief! Perhaps for auld lang syne? What kind of auld lang syne? I was miserable the whole two years! Maybe I thought I was going to write about all that unhappiness. Although I’ve never even looked at the damn thing again. Until now. When I took a picture of it [see above ] to show you.

Oh, my God! You know what? I saved, and just photographed, the wrong brief! This is the brief to the trial court — the one that lost. I made a mistake. The winning brief is back in Dead Storage in Boston.

*********************

So I can begin to throw stuff out. I can begin with this. Out, losing brief, out! Boy, does that feel good!

Now what shall I throw away next?

I actually found this interesting –though the introductory material could have been lopped, with no loss to mankind (generic: includes womankind, of course). And boy, am I glad that I never followed the suggestion made by a well-meaning?/sadistic? friend that I would make a good lawyer….

Teaching physics –even though it didn’t pay as well, and entailed many hours of ‘homework’ every evening and much of every weekend–was a breeze in comparison, it seems. And so much more interesting. Inherently, beautiful, too. The idea that the physical world can be described by mathematical equations is awesome, even a bit weird and creepy. It gives me goose bumps.

LikeLike

Does your first sentence mean you really have nothing left to throw out?

I understand you chose physics and mathematics. With intent. And I’m glad you chose well. By contrast, I backed, or was backed by circumstances, into law in mid-life. (Something like Custer’s last stand.) I began when young by majoring in novel-reading, and did as much as I could, for as long as I could, with that. However, one never knows what lies ahead.

But thank you for actually reading this post. I had my doubts that anyone would. So in a way, the Farmland brief — even the wrong one — served some purpose in my life. And now it’s in the recycling bin, where it will do some environmental good at last!

LikeLike

Just to let you know Gwen is not the only person who found your post interesting 🙂

As part of a decluttering we have been trying to throw out a completely dysfunctional piano. Our oldest granddaughter (who we cannot recall ever having played it) objected strongly to Mrs T. She is nicer than me so it is still here.

Said granddaughter has now pressed her advantage by turning up this morning with a 2 foot by 2 foot sound amplifier, a whiteboard and a mysterious bag of ‘stuff’ for us to store for her. Her argument is that we now have more spare space than she has because we have decluttered. Needless to say Mrs T finds this completely convincing. I am just maintaining a dignified silence…

LikeLike

Oh, Mr. T! Shall I construe your very welcome comment as encouraging me NOT to declutter? Unlike your granddaughter, my four grandchildren are, alas, too young to try to profit from any new spare space in the basement, as they are still all six and seven, although one will be turning eight in March. I therefore fear I shall have to continue to discover things to throw away for quite some time! (Not without writing about them first, though.)

Be that as it may, I am indeed grateful for your articulated interest in this post. The stats show seven anonymous views of it in Canada today, but who knows what those silent Canadians thought? So once again, welcome! And comment away all you like! 🙂

LikeLike

No I am all in favour of decluttering. However my distinct impression is that Mrs T and I have extensive ownership responsibilities for, but limited ownership rights over, what we all too easily slip into thinking are ‘our’ possessions.

Our son and daughter were always willing to concede that we had every right to pay for, buy, repair and clean the house and its contents. But they do draw the line at any unauthorised disposal, especially of stuff from ‘their’ rooms (i.e. the ones they left over 20 years ago). Similarly our 5 year old grandson shows every sign of believing that the kitchen clock, my study clock, the washing machine and a Thomas the Tank Engine set that runs in the window of a local shop are all his.

Have a happy Christmas 🙂

LikeLike

You too! 🙂

LikeLike